Article in The Age 20 March 2011:

Intensive care specialist William Silvester knows better than most that dying with dignity is as important as living with it.

'WHAT on earth are we doing here?'' I asked myself. It was 11 o'clock on a bleak winter Sunday morning in 2001. In the middle of my ward round as the intensive care specialist on duty at Melbourne's Austin Hospital, I was standing at the bedside of one of my patients, John, a 76-year-old man with advanced cancer. He had been admitted to the intensive care unit two nights earlier after becoming dangerously short of breath.

One of my junior doctors had been called to see John at 3am and had quickly established that he had pneumonia. It was clear John would die if we didn't do something to help him breathe. So the young doctor did what he was trained to do; he gave John some medication to drift off to sleep, carefully fed a breathing tube down his throat into his trachea and, with the help of the intensive care nurses, connected the tube to a mechanical ventilator to push oxygen into his sick lungs.

Now, two days later, John was not getting better. In fact, he was slowly but surely getting worse: he needed more oxygen, the ventilator was working harder to push air into his lungs, his white cell count - crucial for fighting infection - was alarmingly low, and his blood circulation and kidneys were shutting down. His body, ravaged by the cancer that would certainly kill him, was also worn out by the chemotherapy he had been receiving.

His oncologist was keen for ''everything'' to be done but the consensus among the ICU doctors and nurses was that John had no hope - he was going to die, despite our best efforts. So there I was, contemplating how we wound up in this situation, when I turned around to see John's wife and daughter standing in the doorway quietly watching me. ''We're not winning the battle,'' I told them gently. It was like someone had finally given them permission to speak. Both women, with tears in their eyes, then told me that John would never have wanted any of this. But no one had bothered to ask.

This, and many other depressingly similar episodes, started me questioning what we were doing. As an intensive care specialist I am responsible for ensuring that all the extraordinary medical technology I have at my disposal is used wisely. My duty of care as a doctor is first and foremost to act in my patient's best interests. In cases like John's, I was clearly failing. There had to be a better way. I wanted to know what my patients wanted before they got too sick to tell me. I certainly had some thinking to do.

I started searching the medical literature and became familiar with the term ''advance care planning''- asking patients ahead of time what medical treatments they would want, and not want, if they became too sick to tell me themselves. It seems so simple, but doctors all over the world have been grappling with the same ethical dilemma for years.

A year later, in 2002, advance care planning was launched at the Austin Hospital. We called the program Respecting Patient Choices, which captured the essence of how we wanted to care for people at the end of their lives. Nearly a decade on, there are RPC programs at many hospitals and nursing homes in Victoria and interstate, and thousands of Australians now have advance care plans.

It didn't take long before we started seeing results on the wards of the Austin. The secret to our success is that we have trained our doctors and nurses in how to have these sensitive, personal and, let's face it, confronting discussions. It isn't something you get taught at university; it is a skill most of us have to consciously work on.

Crucially, we make sure the forms the patient fills out documenting their wishes are kept in a prominent place in the medical records so doctors and nurses can find them if an urgent medical decision has to be made.

SO HOW is it working for patients? Recently we had a 68-year-old man (I'll call him Robert) who had progressive lung fibrosis - scarring of the lungs that ultimately leads to death - who wasn't responding to treatment. He was approached by one of the trained staff but said he wasn't interested because, in his mind, he was going to get better.

About six months later, after several more admissions to hospital, he was approached again and this time he had a very different answer. ''I know I'm not getting better,'' he said. ''Please make sure that if I come back to hospital I don't get one of those breathing tubes or end up in intensive care; please just keep me comfortable.''

He discussed his wishes with his GP and his wife. And eventually, when he did become acutely breathless at home, he asked his wife to call the GP not the ambulance, as he would have done previously. His GP visited him at home, provided comfort care and Robert died with his family at his bedside. That's what I call a ''good death''.

When I speak to young doctors fresh out of medical school, the first thing I tell them is that their duty of care to their patients under common law is to ''take reasonable steps to save or prolong life or act in the patient's best interests''.

I tell them that the critical point is that doctors should not prolong life if it is not in the patient's best interests. And one of the most important considerations of a patient's best interests is what would the patient want if they could have a say.

This means that the patient's views come before the family's. This can be treacherous terrain for doctors and it is easy to be pressured by families who want ''everything'' to be done.

Some years ago, we had a young woman who had advanced cancer in the abdomen. Despite surgery and chemotherapy, she was slowly dying. One day, she was bleeding from the bowel. She said ''enough'', but her husband demanded that the doctors do everything possible. So the full might of our medical armoury was deployed and to what end? This poor woman had various invasive procedures, was given blood transfusions and, in the end, she died in the intensive care unit. Hers was not a good death. She suffered right until the end. Many of us felt terribly conflicted about what she had been put through.

When we talk to a patient about advance care planning, the first thing we do is make sure that they and their family have a good understanding of their diagnosis and treatment options. We find out what their goals and beliefs are and how these may influence what they may want, or not want, if they became really sick. We then ask them to choose someone - a family member or a close friend - to be their substitute decision-maker if required in the future. Finally, if we think that it would be reasonable, medically, to resuscitate them if their heart stops, we ask if they would want that. We ask this question not just because we need to know their wishes but also because most people have no idea what the real chances of success are when we try to get their heart beating again.

The public have an understandable, but entirely false impression, gleaned from TV shows like ER and House, that cardiopulmonary resuscitation will save them. The reality is that, overall, less than 15 per cent of people survive, especially those who are already sick in hospital. WE DON'T talk about death; it is one of society's last taboos. That's why TV shows can get away with scripts that are entertaining but bear no relation to my world as an ICU specialist. For instance, many Australians probably believe they are going to die because of a sudden, dramatic event like a car accident or a heart attack. Wrong.

About 85 per cent of us die after a chronic illness like dementia and up to half of us are not in a position to make our own decisions when we are close to death. It's also unlikely that even after a drawn-out illness our family will know our views about how we want to die, unless we have talked about it.

Finally, a doctor who is confronted with a very sick person and has to make a decision about what to do will probably treat aggressively. Doctors are hard-wired to save lives.

But things are changing. One of our advance care planning nurses who works on the hospital's oncology ward was having a discussion with a middle-aged women with cancer.

''What are your goals at this time?'' the nurse asked. The woman didn't hesitate: ''I want to get home for my daughter's 21st birthday.'' But she was receiving chemotherapy and, as a consequence, was constantly vomiting, was weak and bed bound. The quality of what was left of her life was zero.

So our nurse spoke to the woman's oncologist, who agreed the chemo did not appear to be working. The decision was made to stop it. Instead, she was prescribed strong anti-vomiting medication and various therapists got involved in this woman's end-of-life care.

She got home for her daughter's 21st birthday party. Then a few days later, as expected, she deteriorated and returned to the Austin, but this time, at her request, to the palliative care unit, where she died soon after.

What is certain is that even if the chemo had continued, she would have died in the same time frame but without making it to her daughter's birthday, which was, in the end, all she wanted. Some people might wonder if this isn't euthanasia by stealth. It's not. Euthanasia is the deliberate taking of someone's life, using an active means, where that person would not otherwise have died. Advance care planning is giving people the opportunity to guide doctors ahead of time about whether they would want treatment if they are diagnosed with a severe or progressive life-threatening illness. In that circumstance, if the person dies it is due to their illness.

We all have a right to determine what happens to our body - whether you have cancer and turn down chemo or surgery, kidney failure and reject dialysis, or emphysema and choose not to go on to a breathing machine next time a severe breathing attack occurs. In the same way we have a right to choose now, we also have a right to guide doctors in the future.

The icing on the cake is how advance care planning for end of life also improves the care of patients' families. We did a study at the Austin Hospital, published in the British Medical Journal in March last year, which showed that RPC significantly reduced the incidence of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in the surviving relatives of patients who died.

ONE week ago, nearly 10 years after I stood at John's bed, watching him connected to a ventilator, unconscious and unable to say goodbye to his loving wife and daughter, I am looking after Madeline in the ICU. She was admitted to the Austin Hospital urgently last Christmas Eve because she was struggling to draw air through her voice box and needed emergency help with her breathing.

It rapidly became clear that Madeline had cancer of the larynx and on New Year's Eve she had a laryngectomy and was given a tracheotomy, a permanent hole in her neck to breathe through. That all sounds straightforward and, indeed, it saved her life.

What I haven't told you is that Madeline is 81 years old, she's legally blind and she had been living with her older brother. They relied on each other to survive. We are now two months down the track, Madeline still hasn't learnt how to speak using the voice machine, she still requires feeding by a nasogastric tube - a tube through the nose into her stomach - and, most importantly, she is withdrawn and not fully ''compos mentis''.

A crossroads has been reached. Madeline is not going to be able to go home. She will not regain the ability to eat and swallow enough food to stay alive.

The surgeons had spoken to Madeline and her next of kin and said that they wanted to put in a PEG tube, a permanent feeding tube into the stomach through a hole in the skin. Through sign language, Madeline said she did not want the new tube, wanted the nasogastric tube out and no longer wanted treatment.

Her son, as her appointed medical enduring power of attorney, agreed, saying that before Christmas Eve his mother had told him she would not want to go on if she could not remain fully independent at home.

Madeline was referred to me through one of the hospital's advance care planning staff. It was evident that although she no longer had the mental capacity to sign legal documents or make major medical decisions, she was consistently clear about what she did not want. I met the surgeons and then we met the family, and told them that we supported their views. We did not think that Madeline would regain the ability to talk, eat or live at home, and so it was appropriate to remove the feeding tube and refer her to palliative care.

I would not have expected a referral like this in the past. Care at the Austin Hospital has certainly come a long way. And there is still a way to go.

The following letters were in the Senior - Victorian edition - April 2011:

THREE letters in The Senior’s February (2011) issue dealt with euthanasia.

The first two made it clear they had not walked this path, either personally or with a beloved older relative. Neither have spent years visiting a hostel or a nursing home.

If they had, they would know there is very little human dignity left in the lives of our elderly, however gentle and humane the dedicated staff are.

I have sat with people, still of sound mind and not depressed, simply saying “enough is enough, I am waiting to die and I would like just to go to sleep knowing my passing will be painless”.

There is no dignity in dribbling down your shirt front, in not being able to shower yourself, not having control of your life after 80-plus years.

There certainly is no dignity in incontinence, even if the incontinence industry invents a new product every week.

Civilisation has consistently evolved towards greater humanity. We have not perfected it but this has always been the goal. There is no question of people being bullied into dying; simply that those of sound mind, who have made this decision, should be able to carry it through.

This is not a negative attitude. It gives us power and removes the fear that most of us have about how we will die.

Palliative care is simply a much slower course to death.

I Jones, Heathcote.I am one of the 85 per cent of people who favour euthanasia.

I am sure Florence Nightingale was aware of it in the Crimea.

I wish I had met one of those doctors who use the softly-softly method when my father was dying a slow death.

The people who advocate euthanasia are not scaremongering; they are providing a sevice to the sick and dying.

I feel sorry that Paul Russell (Your Say February 2011) is so nauseated by the number of people who want to have this choice.

I hope that I can find a doctor, if I need one, to assist me in my departure from this world to put an end to my misery to help my family.

That’s humane; that’s reality; it’s also an educated choice.

Eileen Lindsay-Stewart, Traralgon

Editorial in The Age 3 April 2011

Medical intervention is not always the right choice.

DOCTORS are hard-wired to save lives, wrote Dr William Silvester in The Sunday Age. But when a patient is chronically ill, and suffering from an incurable condition, should doctors do all they can to extend life? Dr Silvester, director of Respecting Patient Choices at Austin Heath, has come to question whether aggressive medical intervention is always the right way to proceed.

His thoughtful article about the need to respect what a patient wants struck a chord with many readers, who have welcomed this gentler approach to patient care.

Over the past 10 years, the Austin, along with other hospitals and nursing homes around Australia, has developed programs to learn how patients would wish to be treated at the end of their lives. ''Advanced care planning'' asks patients what they would want - or not want - if they become too sick to tell the doctor themselves. At the Austin, Dr Silvester says, doctors and nurses are trained to have ''these sensitive, personal and, let's face it, confronting discussions''. ''It isn't something you get taught at university; it is a skill most of us have to consciously work on,'' he says.

Adding to the difficulty is that many patients have not had these discussions with their own families. Dr Silvester says a patient's wishes should come before the wishes of their relatives. But he warns this can be ''treacherous terrain'' for doctors, who can be pressured by families to do everything to prolong life.

The letters received by The Sunday Age strongly supported Dr Silvester's approach. Many fear that their choices, or those of their loved ones, will be stripped away at the end of their lives. They fear they will be subjected to interventions they would not want and made to suffer unnecessarily. It is a modern dilemma - people are afraid now, not only of sickness and death, but of the possibility that extra suffering will be imposed on them by the medical system itself.

Yet, as Dr Silvester says, everyone has the right to refuse treatment. Many cancer patients willingly undergo surgery and chemotherapy, knowing the painful cost of such treatments, because they want to extend their life if they can. But not everyone wants to keep receiving these treatments indefinitely. Saying no to medical intervention is not the same as euthanasia. But it does give people choices - such as the choice to die at home instead of in an intensive care unit.

We are not comfortable talking about death. Even so, most people would probably want to have a say about their medical treatment during their dying days. In order for our choices to be respected, we need to find the courage to talk to the people closest to us about the kind of care we would want, before it is too late. For their part, hospitals need to be mindful of their patients' wishes. It is still the case that unwanted interventions prolong the lives of the terminally ill, adding to their distress and the distress of those who love them.

Listening to patients takes an effort, and is kinder. A study done by the Austin and published in the British Medical Journal last year showed that its Respecting Patient Choices program had reduced anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in the surviving relatives of patients who died.

Medical science is advancing and our population is ageing. Each year we learn more about how to extend life, and how to improve the quality of our life as we grow older. Inevitably, however, death will come. By listening to patients and respecting their wishes, Dr Silvester and others like him are doing what they can to ensure medical technology does not overpower the people it was designed to help.

Article in The Age 3 April 2011

RON and Jo Lennox have a familiarity with death. Jo saw a lot of it in 39 years of nursing, and she sat in a small room with her father for three days as he slowly but gently passed away after a series of strokes.

Over a two-year period in the mid-1990s, Ron lost his brother, mother, sister and former wife. After years driving trucks, he spent seven more in aged-care facilities, looking after people at the end of their days. He's stared down four heart attacks in the past decade. So death doesn't frighten them - ''billions have done it before us,'' says Ron. It's the dying. Or dying badly. More particularly, dying on someone else's terms.

That was a possibility they had to confront in February when Ron, 69, was diagnosed with inoperable cancer. He had been admitted to the Austin Hospital after three bouts of pneumonia when someone noticed, at the periphery of one of his X-rays, shadows on his liver.

''They did a bit of this and a bit of that, and a bit of testing here and there and they got down to my liver and found I had cancer in it,'' he explains.

It was a secondary cancer from a rapidly advancing stage 4 adenocarcinoma in his bowel, but with his cardiac history and a chronic pulmonary illness it was decided that surgery and major chemotherapy were too dangerous.

He says he didn't realise how serious it was until he received an unexpected visit from a palliative-care nurse: ''I thought, hmmm, this can't be good.''

Ron affects a jokey, matter-of-fact straightforwardness about his illness that on one hand frustrates Jo and, on the other, is one of the things she best loves about him. But he waits until she's out of the room making tea before he tells what happened next.

''They said to me down the Austin, 'You know you're pretty well gone, what do you want to do?' I told them, 'I know what I don't want. I don't want to be kept alive as a vegetable'. ''Sorry, that's me being crude and politically incorrect, but I've seen too many people when I was working in aged care where the families are financially broke, physically and mentally broken down and hurting. And eventually when they die, they've got to go through the grieving process anyway.

''I said, 'Just let me go, I don't want all this bullshit of keeping me alive on pumps and tubes and bloody things'.''

Ron had assigned Jo his medical power of attorney, but after another stay in the Austin last month they got themselves introduced to intensive-care specialist Bill Silvester and asked to sign on to the hospital's Respecting Patient Choices program. This advanced-care plan, launched at the Austin in 2002, gives patients with terminal illnesses the opportunity to say, ahead of time, what medical treatments they want and, perhaps more importantly, do not want. The signed plan is kept prominent in the patient's medical records. Ron said that at the end he did not want ventilation, tube feeding or CPR. He wanted adequate pain relief and, if possible, to die at home with Jo and his family.

Jo says the decision, and the sense of control, have given them comfort, ''rather than just having pain and ignorance, which makes anxiety''.

''Knowing, understanding, gives you a lot of peace of mind. These decisions - not to have aggressive treatment or to withdraw treatment - have been made by the medical profession forever. But it's only really of late that people have realised they can make the decisions and make it legally binding.''

It's not euthanasia, she says, because no one is taking Ron's life. ''But you realise at a particular time that the age process and disease process are meaning that this life is coming to its end. And you acknowledge that and let it be.''

''There's such a thing as quality of life,'' says Ron. ''The Hippocratic oath says we will preserve life. It doesn't say we will preserve quality of life, and that's where the problem's always been.'' But asked how he feels about dying, he reverts to blunt jokiness: ''Mate, I dunno. Never been there. But there's a lot of people dying who've never died before.'' There's a touch of an old-fashioned man's unwillingness to open up about emotions in his response, but mostly it's an attempt to protect Jo. ''Mate,'' he says when she's out of earshot, ''she's doing this pretty hard.''

Jo responds to the same question by saying she's tried to ''categorise'' herself. On one hand, she says, she has put on her nurse's hat, as she did with her dad, and understood that these tough decisions have to be made. ''As nurses, a lot of our exposure to people is at terribly emotional times where there are those decisions to be made and I can make them - and help them make them - out of kindness and necessity. But at the other end of it,'' she says, beginning to cry, ''I'm losing the one I love.''

Not long after receiving the prognosis, Ron was approached by a group of medical students who asked how he was coping.

''Ron couldn't find the words, but I said, 'He's not gone yet and while we have life we will live,'' recalls Jo.

''Whatever level that is, it might just be something simple like holding each other, but we will live, because he's not dead yet.''

That's right, says Ron. This week he began a course of oral chemotherapy, not as a cure but to reduce the symptoms ''because you've got to give it your best shot''. He's trying to keep his morphine to a minimum because if things go unexpectedly well, he doesn't want to come out the other end a dope addict.

''Who knows,'' he says. ''I might be gone in three weeks, but I still might be around in 10 years. It's happened. But there's not much chance. I'm a realist.''

Two letters in the June 2011 edition of the Victorian Senior:

MY BROTHER suffered for years with motor neurone disease and dementia.

I was astounded and angry to read about ‘dignity’ in dying (Peter Phillips, Your Say, May). My brother was buried alive in his own body, aged 67.

What is so dignified when you have to be hoisted onto a bed to have your nappy changed, or having a bath like a six-month-old baby?

He sat in a wheelchair the entire day, unable to speak or take part in any activity, even though his brain was still intact at the time.

In the latter stages of his disease, when parking the car in front of the nursing home, I could hear him screaming like a wild animal, starting at 7am and often until 11.30am, upsetting the staff and other patients.

Toward the end he could not swallow his food or close his eyelids. One would not wish having to die like this onto his worst enemy, never mind a relation!

I am a volunteer in a nursing home. Many patients, no matter how well cared for, tell me they want to go.

At 70, I am all for Dr Nitschke and can’t wait for Australia to ‘grow up’ like the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, etc.

LS, via email.

Millionaire hotelier Peter Smedley named as man whose Dignitas assisted suicide was filmed by BBC

By Gordon Rayner - Chief Reporter - Daily Telgraph (UK)

A few days after Peter Smedley’s death last December, his close friends found individually-written letters from him in their post, telling each one how much they had meant to him.

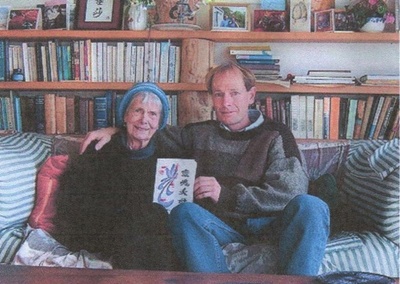

Peter Smedley pictured with his wife

Mr Smedley, a millionaire hotelier and scion of the Smedley’s tinned food empire, had been such an intensely private man that none of the recipients had known in advance that he had planned his own assisted suicide and travelled to the Dignitas clinic in Switzerland to end his life.

But the greater surprise was still to come, when Mr Smedley’s friends were joined at his memorial service by a BBC crew who had filmed the 71-year-old’s final moments for a controversial new documentary by Sir Terry Pratchett, the author and campaigner.

“We didn’t know until after the event that he had gone to Dignitas, and we didn’t know about the film until we went to the memorial service and the film crew was there,” one of his closest friends said last night.

Mr Smedley, who was suffering from motor neurone disease, is referred to only as “Peter” in the BBC2 film, Choosing to Die, which will be broadcast on Monday. (June 2011 UK)

Until now, his full identity has remained a secret, but his friends have told The Daily Telegraph of his determination to help change the law on assisted suicide and paid tribute to his courage.

Related Articles“Peter was an extremely private man and not someone that would want to share most things,” said a close friend, who asked not to be named. “But clearly he wanted to change the law.

“I think he was very keen for people in that predicament to be able to make a decision on when to end their lives, and you can’t do that in England because your wife or spouse isn’t allowed to help, and it’s a terrible thing to have to go to Switzerland.

“He would have wanted to die in his own bedroom or his own sitting room.”

Unknown to all but his closest family, Mr Smedley invited Sir Terry to accompany him and his wife Christine, 60, to the Dignitas clinic in Switzerland, where he drank poison and died on Dec 10 last year.

His death will be the first assisted suicide to be screened on terrestrial television in the UK.

Sir Terry, who has campaigned for the legalisation of assisted suicide since he was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, said in an interview this week that he was sure Mr Smedley would still be alive if he had been able to kill himself in his own home, rather than having to go to Switzerland while he was still fit enough to travel.

“I’m sure that’s true,” said his friend. “I’m sure both he and his wife would have preferred it if he could have made the decision to die here.”

Mr Smedley grew up on his family’s farms in East Anglia, where he would help pick the peas that Smedley’s were famous for before the brand eventually became part of Premier Foods.

As a young man he moved to South Africa, where he became a pilot and flew a single-engined aircraft across the continent, before moving back to England and establishing a property empire.

After marrying Christine in 1977, with whom he later had a daughter, now aged 20, the couple bought Ston Easton Park in Somerset from William Rees-Mogg, the former editor of the Times, and converted it into a luxury hotel.

Within a year of it opening in 1982 it was named Hotel of the Year by the food critic Egon Ronay, and they later established it as a major venue for horse trials.

The couple retired to Guernsey in 2000, where Mr Smedley was diagnosed with motor neurone disease two years ago.

“A lot of his friends didn’t know he had been diagnosed with it to begin with,” said his friend. “He didn’t want people to feel sorry for him.

“He did a lot of research into motor neurone disease and knew there was no cure and that it leads to a horrible death and a ghastly future to face. He would have ended up suffocating and that’s obviously what he wanted to avoid.”

In an interview in this week’s Radio Times, Sir Terry said of Mr and Mrs Smedley: “They are of a class and type that gets on with things and deals with difficulties with a quiet determination.”

Moments before Mr Smedley died, said Sir Terry: “I shook hands with Peter and he said to me ‘Have a good life’, and he added ‘I know I have’.”

When a Dignitas worker asked him if he was ready to drink the poison that would end his life, Mr Smedley said “Yes” and added: “I’d like to thank you all.”

Sir Terry said that as he was doing this, Mr Smedley became embarrassed because he could not remember the name of the sound man.

“And that’s what puts your mind in a spin,” he added. “Here is a courteous man thanking the people who have come with him to be there and he’s now embarrassed, at the point of death, because he can’t remember the soundman’s name.

“This is so English…it also seemed to me with his wife that there was a certain feeling of keeping up appearances.”

After Mr Smedley died, said Sir Terry: “I was spinning not because anything bad had happened but something was saying, ‘A man is dead... that’s a bad thing,’ but somehow the second part of the clause chimes in with, ‘but he had an incurable disease that was dragging him down, so he’s decided of his own free will to leave before he was dragged.’ So it’s not a bad thing.”

Days later, Mr Smedley’s friends received their letters.

“He wrote about how much we meant to him, and it was a very gentlemanly, very sweet and dignified thing to do, typical of him really,” said his friend.

“I think it was amazingly brave of Peter and Christine to do what they did.”

On Monday the BBC, which has been accused of becoming a “cheerleader” for assisted suicide, defended its decision to show Mr Smedley’s death in the film.

Sir Terry hopes it will persuade the government to think again about the law on assisted suicide, and advocates a system of doctors being able to prescribe take-home suicide kits to enable terminally-ill people to choose the right moment to end their lives.

Christine Smedley said last night she did not want to discuss her husband’s death.

The BBC has been flooded with complaints after it screened Choosing to Die, a documentary showing a British motor neurone disease sufferer taking his own life at a Swiss clinic.

14 Jun 2011The corporation said 898 people had registered their disapproval of the documentary presented by the author Sir Terry Pratchett, with 162 fresh complaints since it aired on Monday night.

A spokesman added that it had also received 82 “appreciations” of the programme about Peter Smedley, a British motor neurone disease sufferer, who allowed the film crew to capture his dying moments at the Dignitas clinic.

Here are some of the comments in condemnation and support of the film, which has reignited the debate on Britain’s assisted suicide laws:

Related Articles“I was appalled at the current situation. I know that assisted dying is practised in at least three places in Europe and also in the United States.

"The Government here has always turned its back on it and I was ashamed that British people had to drag themselves to Switzerland, at considerable cost, in order to get the services that they were hoping for."

Alistair Thompson, a spokesman for the Care Not Killing Alliance pressure group: "This is pro-assisted suicide propaganda loosely dressed up as a documentary. The evidence is that the more you portray this, the more suicides you will have." Charlie Russell, who directed the documentary:

"As a film-maker I felt that it was the truth of the matter. Unfortunately we do all die. It's not necessarily very nice but that is what happens to us all so I think it is quite important to see it."

Rt Rev Michael Nazir-Ali, the former Bishop of Rochester: "I think an opportunity had been bypassed of having a balanced programme – the thousands of people who use the hospice movement and who have a good and peaceful death, there was very little about them.

"This was really propaganda on one side. Life is a gift and it has infinite value and we are not competent to take it, we do not have the right to take it, except perhaps in the most extreme circumstances of protecting the weak.”

Dignity in Dying, the pressure group: "People who did not want to watch it did not have to watch and were not confronted with something they did not want to see.

"It certainly shows that Dignitas is not an ideal option for people and we would rather people had the choice of dying at home at a time and in a manner of their choosing."

Dr Peter Saunders, campaign director for the Care Not Killing Alliance: "We felt the programme was very unbalanced and one-sided and did not put the counter-arguments. Our biggest concern was that it really breached just about all the international and national guidelines on portrayal of suicide by the media.

"We are very worried about the danger of copycat suicide or suicide contagion. We have written to the Secretary of State for Health and the Secretary of State for Culture to ask them to carry out an urgent investigation into the way that assisted suicide has been covered by the BBC and its link to English suicide rates."

Debbie Purdy, a multiple sclerosis sufferer and assisted suicide campaigner: "Lawyers and judges have been the only people who have been prepared to defend my rights and my right to life and the quality of my life is the most important thing to me.”

Liz Carr, a disability campaigner: “I, and many other disabled older and terminally ill people, are quite fearful of what legalising assisted suicide would do and mean and those arguments aren't being debated, teased out, the safeguards aren't being looked at.

"Until we have a programme that does that, then I won't be happy to move onto this wider debate."

Emma Swain, the BBC’s Head of Knowledge Commissioning: “The film does show some other perspectives but it is not critical that every film we make is completely impartial and balanced.”

Nola Leach, chief executive of CARE: “I rather thought that we had moved on from the days when people gathered in crowds to watch other people die.

“That the BBC should facilitate this is deeply disturbing. One wonders whether the BBC has any interest in treating this subject impartially.”

BBC viewer, writing on the corporation’s Points of View message board: "What a brilliantly paced, thoughtful, informative and fascinating programme that was. The contributors' accounts were very moving and strangely uplifting. Uplifting in that it was THEIR decision to die.”

Damian Thompson, Editor of Telegraph Blogs: “As for the BBC, I wonder what the moral status is of exploiting a writer with a degenerative brain disease to nudge us towards a creepy change in the law – at our expense, of course.

“I would threaten to withhold my licence fee in protest, but the Beeb is utterly relentless in tracking down evaders and the last thing I want is to wake up in a Swiss clinic with a syringe staring me in the face.”

BBC viewer, writing on the corporation’s Points of View message board: “I’ve watched it and applaud Terry Pratchett for allowing us to debate this important issue. I hope we will look back upon this era in a few years time and wonder how we could have allowed people to die without dignity.”

Obituary in The Age 7 JUNE 2011

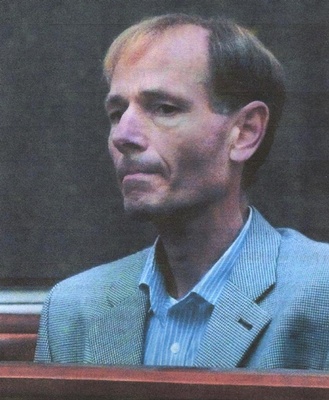

JACK Kevorkian, the American pathologist who attracted considerable notoriety through his strenuous efforts to assist the terminally ill to end their lives, has died of a pulmonary thrombosis in hospital, aged 83.

A macabre embodiment of society's moral confusion over the issue of voluntary euthanasia, Kevorkian, a gaunt, white-haired figure was dubbed ''Dr Death'', ''Jack the Dripper'' and ''The Avon Lady from Hell''. He had endured a long struggle with heart and kidney problems.

Since law forbade him to kill the terminally ill at their request, he provided the facilities, demonstrated the apparatus of self-destruction, and then watched.

Kevorkian claimed to have helped about 130 people to commit suicide. In 1999, after the American television show 60 Minutes broadcast a videotape he had made of the assisted suicide of a 52-year-old man, he was convicted of second-degree murder. He served eight years in jail in Michigan.

Renowned for his good humour, Kevorkian termed himself an ''obituarist'', the first of a new variety of medical specialist who would assist the terminally ill to kill themselves under strictly controlled guidelines, a process he termed ''medicide'', or physician-assisted suicide.

For his first assisted deaths in 1990, he used a machine he called a ''thanatron'', an apparatus that pumped saline into the ''client'', switching to a lethal solution when the client pressed a button. After he had used it three times, the complicated apparatus (he is pictured with it in February 1991) was confiscated and in 1991 his Michigan state medical licence was revoked, preventing him from buying drugs.

He then switched to the simpler, and less expensive, process of gassing by carbon monoxide, calling the machine a ''mercitron''. Kevorkian said the latter method imbued a pinkish tone to the flesh that left the dead body ''better looking'' than it had been in life. Kevorkian became a cause celebre during his trial. His lawyer at the time, Geoffrey Fieger, compared him with Socrates, while prosecutors warned that this was the first step on the slippery slope to genocide. As Ron Rosenbaum, whose Travels with Doctor Death became a landmark essay, asked: ''Is this the trial of Socrates or Dr Mengele?'' It was a loaded question that Kevorkian himself did little to defuse.

Some were surprised to detect a note of paranoia in his outbursts against his opponents and journalists - he constantly compared himself to Galileo - since he was sometimes treated with deference, and even affection, by the American media.

But he was vigorously opposed by pro-life lobbies, the authorities and even by those in favour of voluntary euthanasia, who considered that Kevorkian's morbid fascination with the point of departure cast their cause in an unfavourable light. In reviewing Kevorkian's book Prescription Medicide: The Goodness of Planned Death, even the vociferous supporter of voluntary euthanasia, Ludovic Kennedy, observed: ''I wish another than he had invented the 'mercitron'.''

Kevorkian's supporters pointed to the ageing population and the ability of modern medicine to prolong life almost indefinitely, at astonishing cost; and even his detractors admitted that his activities ensured that the issue of euthanasia remained in the public conscience. Born in Pontiac, Michigan, to parents who fled the Turkish massacre of Armenians in 1915, Kevorkian established his credentials as a contrarian in high school during World War II by learning both German and Japanese.

After gaining his medical degree from Michigan University in 1952, he served as an army doctor, first during the Korean war and then in Colorado. He apparently taught himself to speak seven languages, painted in a disturbing but original fashion using his own blood, played three musical instruments and became a devotee of Bach. He played the piano and the flute on his composition The Kevorkian Suite: A Very Still Life, a jazz disc released to bemused reviews in 1997.

One of his two sisters, Margo, later helped in his medicide practice, often videoing the patients as evidence that the procedure was carried out at their explicit request.

During the 1950s, Kevorkian became somewhat isolated from his colleagues, and began to advocate increasingly controversial measures: the use of the organs of condemned prisoners for experimentation, the use of their living bodies (under anaesthetic) for research, and blood transfusions from cadavers. His proselytising for better use of dead bodies extended to visits to death row at a prison in Ohio to persuade the convicts to consider euthanasia in the hope that their organs could be reused.

Kevorkian then went to practise in California, attempting to make a film about organ harvesting, but finally drifted back to Michigan, where he found himself unemployed. He wrote articles for a German magazine, Medicine and Law, appearing to condone some doctors in concentration camps because they advanced medical knowledge in the face of otherwise useless destruction. In 1961, he stirred controversy by using blood from recent cadavers for transfusions. Time magazine called it ''blood from the dead''.

In 1989, he demonstrated his ''suicide machine'' on television and had business cards printed advertising his services - but he never accepted payment.

His first client, Janet Adkins, was a 53-year-old who suffered from Alzheimer's disease; she died in a Michigan forest in the back of his Volkswagen camper van in 1990.

Over the years that followed, Kevorkian continued to practise exclusively in Michigan, where he assisted sufferers from cancer, Alzheimer's, arthritis, heart disease, emphysema and multiple sclerosis through the final exit. Among them were a disproportionate number of women.

The more the authorities attempted to restrain him, the more publicity he garnered - and the more requests for assistance he received. Kevorkian claimed that he found his work exhausting: ''You really couldn't do one a day of these. It just takes too much work.''

By November 1993, despite the introduction of laws in his home state of Michigan banning him from assisting in a suicide, Kevorkian had helped 19 people take their own lives. He was unsuccessfully tried by prosecutors four times before finally being imprisoned in 1999. In 2008, Kevorkian ran for the United States Congress as an independent, but secured less than 3 per cent of the vote.

Last year Al Pacino won an Emmy award for starring as Kevorkian in the HBO film, You Don't Know Jack.

Kevorkian was unmarried and has no immediate survivors. TELEGRAPH, GUARDIAN

Do people have the right to choose when they die? Should the State condone the deliberate termination of any person’s life, including those who are terminally ill and want to bring about their own death?

The euthanasia debate has been thrust into the educational spotlight with the release of a video for sale into schools worldwide.

Produced in England by Melbourne-based VEA, the 25-minute documentary titled Euthanasia, highlights prominent euthanasia activists, including Dr Phillip Nitschke and Britain’s Lord Joel Joffe, Dr Michael Irwin, Baroness Jane Campbell and Alistair Thompson.

The program covers definitions of euthanasia and laws surrounding it, the medical perspective, religious attitudes, non-religious attitudes, and a range of pro- and anti-euthanasia arguments.

The video package also includes an eight-minute drama, which portrays a terminally ill young person who makes a controversial decision in favour of assisted suicide.

The program made news in London’s Daily Mail earlier this year, where its main headline described Dr Nitschke as a “Euthanasia fanatic” and suggested he gave a “workshop on how to kill yourself” in the video, which the headline claimed was “for 14-year-olds”.

VEA’s producer of the program, Thomasina Gibson, said the headlines were not truly representative of the production and its intended audience and use in schools.

“The program gives equally balanced views on the euthanasia debate and does not attempt to promote one side ahead of the other”, she said.

Dr Nitschke, who founded Exit International, was the first person in the world to legally administer a voluntary lethal injection under the short-lived laws that saw euthanasia legalised in the Northern Territory during the 1990s.

In the video, Dr Nitschke says that under Australian law it is clearly illegal to advise, assist or counsel anyone to take their own life. Providing information to people, he argues, does not breach that law.

“If you give people accurate information, you’re not encouraging them to suicide any more than you’re encouraging them not to suicide”, he said.

“What you’re doing though is putting them in a position where they can make a rational, informed choice.”

Baroness Jane Campbell, a commissioner of Britain’s Equality and Human Rights Commission, was diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy as a baby and was not expected to live beyond the age of two.

She says recent research in the UK shows that 81 per cent of people who request assisted suicide do so for the primary reason that they don’t want to be a burden.

“It has nothing to do with their medical condition,” she said. “And I think that tells us a little bit about the society that we are operating in.

“It’s a society that says if you can’t walk and you rely on someone to help you to the toilet, that somehow you’re a second class citizen, expensive – an economic drain.”

Dr Michael Irwin, former United Nations medical director and ex-chair of Dignity in Dying, is a long-time advocate of voluntary euthanasia.

Five years ago he was struck off the British medical register after admitting to helping a terminally ill friend to die. He claims to have provided such assistance to at least 50 terminally ill patients.

“How much people suffer at the end is purely a personal decision – no one else can do it for anyone else”, he said. “Especially if someone is terminally ill and there is no way to reverse the dying process, it should be their personal choice if they want to go”.

Alistair Thompson from Care not Killing says there have been instances in Oregon, USA, where assisted suicide is legal, of “bean counters” deeming it more economical to end someone’s life than provide them with access to expensive life-extending drugs.

“If you open the floodgate to legalisation of assisted suicide, yes there might be some people who want to die, but there will be others who feel pressured into dying because they are a care burden or a financial burden,” he said.

Following the Euthanasia program’s global launch in Bristol in January, VEA held a Melbourne launch in February where Dr Nitschke was joined in a panel discussion by Dr Mathew Piercy representing Right to Life, Ms Gibson and VEA executive producer Simon Garner. More than 100 students and educators attended.

*For information about buying a copy of the program for personal or educational use, phone VEA on 1800 034 282 (business hours), or email vea@VEA.com.au. Mention The Senior to receive a 15 per cent discount off the purchase price.

Peter Phillips (Your Say, May 2011) doesn’t get it. No one “yearns for euthanasia”.

Everyone hopes for a peaceful, painless death.

Death is a reality, but a slow, painful death can cause the “human person” into forgoing their dignity.

Mr Phillips suggests those in homes who are “miserable” should just pull up their boot straps, accept the kind charity handed out, realize they are letting down the “great Australian fighting spirit” and allow those of us bystanders off the hook.

No one wants to watch people being miserable.

Neil Francis and Dr Phillip Nitschke only offer help to those who actively seek it. People who wish to lie suffering and wait for a natural release already have the right to do so; but others who do not wish to suffer should have the same rights.

What is this “human dignity” that over-rides everything else? Lying in a bed unable to control any bodily functions?

Some of us want to know that if we are in for a lot of pain and suffering in the end, we can cut it short if we do not want to lie there waiting..

A Cassell, HeathcoteSHOULDN’T the euthanasia debate be all about personal choice?

Does Peter Phillips realise that he himself has no choice in this matter?

To have a choice you must have an alternative; but there is none.

If there was, everyone could choose what they felt was right for them without having someone else’s view forced on them, as at present.

Wouldn’t this be better than this rhetoric about a depressing picture, yearning for euthanasia, real dignity, the great fighting spirit or doctors of death who lost the plot?

Let’s debate if we want personal freedom and personal choice, not someone else’s choice.

W Paschke, Riddells Creek.Peter Phillips stated that for the sick, elderly and neglected, “hope can always be found”.

As a daughter who cared for both parents before they went into nursing homes, I disagree.

There was no dignity for them.

A typical day would be: ring the buzzer for someone to take them to the toilet; no one comes, have an accident in bed, and wait to be taken to the shower, feeling degraded.

After the shower, sometimes be left with only a towel draped over them while the staff person attends to someone else.

When they were finally dressed for the day, what did they have to look forward to? Only my visit.

My parents didn’t have dementia, so they knew exactly what was happening to them.

They were in care for years and hated every minute of it, every day, and told me many times they could just close their eyes and die.

So Peter had better pray he doesn’t end his weary days telling his loved ones he just wants to end it and be at peace, while he sits day after day knowing hope will never be found.

Charlotte Williams, Rosebud.

ALAN Rosendorff knows the value of a peaceful death. When his first dog Jimmy was battling a terminal illness 45 years ago, he took him to the vet who had looked after him since he was a pup.

''The vet laid him down on his table and said 'I'm sorry old soldier, I've known you for 15 years, but it's time to go.' He died painlessly and comfortably with the vet talking to him the whole time. It left such an impression on me,'' said Mr Rosendorff of the death he witnessed as a teenager.

Now, aged 58 and dying of cancer, Mr Rosendorff is wondering why a doctor cannot show him the same kindness.

Melbourne lawyer Alan Rosendorff, who has terminal cancer and faces a long, painful death has asked the Premier to initiate a public debate on voluntary euthanasia.

Photo: Jason SouthWith just months or possibly weeks to live, he has requested a meeting with Premier Ted Baillieu to express his frustration that he and others like him cannot access voluntary euthanasia. Above all, the Melbourne lawyer wants the government to ask the Victorian Law Reform Commission to examine the issue so Victorians can have an informed debate similar to that which preceded the decriminalisation of abortion three years ago.

In a letter delivered to Mr Baillieu's office yesterday, he said that after living a life full of choice about how to live, he is now denied a choice about how he wants to die.

''The disheartening reality is that as my illness progresses towards death it is quite possible, indeed likely, that I will experience intolerable and uncontrollable pain and suffering, despite the excellent quality of palliative care available to me,'' he wrote. ''There is no legal choice that I can exercise to peacefully bring my life to an end in a way, if and when I am ready, that is to my mind appropriate and humane.''

A spokesman for Mr Baillieu said he would urgently consider Mr Rosendorff's request. In an interview with The Age, Mr Rosendorff said he was facing an ever increasing amount of physical and existential pain stemming from cancer in his stomach and lungs.

Since being diagnosed with an aggressive tumour in the join of his stomach and oesophagus two years ago, he has undergone stomach surgery and several rounds of chemotherapy, which led to a heart attack in 2009.

The surgery, which removed part of his stomach, has left him with little control over his bowel and he feels constantly nauseous despite being on a diet of only powdered food and soup. He has lost 30 kilograms, feels weak and cannot tolerate many drug treatments that produce side effects worse than those of his illness.

Mr Rosendorff said the most distressing symptom of his disease was an intermittent bubbling of acid up his throat which forces him to sleep upright at night to avoid choking.

''Almost every night, I slip down at some stage and when that happens, I start drowning in acid. It is the most ghastly feeling, you can't breathe because your lungs fill with acid and it burns your mouth.''

Two grapefruit-sized tumours in his lungs also trigger sudden, searing pain when they hit nerves.

However, he said all of his physical symptoms pale in comparison to the loss of control, enjoyment and purpose in life that he feels.

''It's the inability to sit at a table and enjoy food with your children, grandchildren and friends. It's the inability to go out on a Saturday night to a restaurant, and if you do, having everyone feel uncomfortable because you can't eat. It's the hurt and anxiety it creates for your family …

'' At the end of the day, these are the things that make me want to exercise a choice.'' If he had the option, Mr Rosendorff said he would choose a path similar to that of his old dog. He feared a slow, painful decline where his life was prolonged because of a carer's religious or ethical urge to avoid interventions that would hasten his death.

''I can't think of a better way to go than to be surrounded by the right people in a loving, safe and warm environment where I'm exercising the choice at the right time for the right reasons.''

Dr Rodney Syme, a Victorian physician who says he has helped many people die despite laws banning assisted suicide, said Mr Rosendorff faced a grim end, which included the possibility of choking or starving to death.

''I'm afraid to say that if the disease goes its full course, Alan faces a bleak future,'' he said.

''If he goes to the end of the terminus, it's an appalling vision, so it's no surprise that an intelligent man like Alan might want to get off the tram one or two stops before that point.'' Neil Francis, president of Dying with Dignity Victoria and head of YourLastRight.com, said it was time the Victorian government listened to its people who overwhelmingly support voluntary euthanasia. The last Newspoll survey of 1200 Australians in 2009 found that 84 per cent of Victorians supported physician-assisted death.

Furthermore, he said, the US states of Oregon and Washington and the Netherlands had shown there were safe models to introduce.

''At the moment, the law lags behind the will of the people,'' Mr Francis said.

However, Right to Life Australia vice-president Katrina Haller said although her group felt compassion for those who were dying and in pain, it signalled a need for more care, not killing. She said proposals to introduce voluntary euthanasia endangered vulnerable people, such as the elderly, the dying, the depressed and the disabled.

''The right to life affirms the dignity of all patients, regardless of illness or disability,'' she said.

''If a person is suicidal, they need proper treatment, possibly for depression. Bills for euthanasia are dangerous in practice and so-called safeguards would prove unenforceable.''

Legislation for voluntary euthanasia has been introduced and defeated or lapsed 12 times in the various states and territories, including once in Victoria in 2008. Such legislation has only been passed once, in the Northern Territory in 1995, but was overturned eight months later by the federal government.

Victorian Premier Ted Baillieu personally agrees with voluntary euthanasia, but says it's a divisive issue that needs to be tackled on a national level.

• Video feedbackDespite personally supporting voluntary euthanasia, Premier Ted Baillieu won't act on his views because it is a divisive issue.

Mr Baillieu has received a letter from terminally ill lawyer Alan Rosendorff requesting a meeting to discuss why he can't legally choose how he dies as he waits in pain for his life to end.

The premier said he had long expressed his support for voluntary euthanasia but would not be introducing any bills to the Victorian Parliament regarding the issue.

"I think if there is to be a resolution about this then it needs to occur at a national level so we don't have jurisdictional differences and we saw that 15 years ago in the Northern Territory," he told Radio 3AW."

A voluntary euthanasia bill was introduced by individual members and defeated in Victoria's upper house in 2008.

Such legislation has only been passed once, in the Northern Territory in 1995, but was overturned eight months later by the federal government.

Mr Baillieu said he did not believe there would be changes to euthanasia laws in the forseeable future, even though polls had shown popular support for reform.

"With divisive issues ... I think it's important that the community support be such that it's not divisive and this is an incredibly divisive issue unfortunately," he said.

Mr Baillieu said there were palliative care measures people in pain could pursue to help ease their suffering.

The premier said he would be in touch with Mr Rosendorff.

Mr Rosendorff said when his first dog Jimmy was battling a terminal illness 45 years ago, he had been given a more humane death than was now available to him.

"The vet laid him down on his table and said 'I'm sorry old soldier, I've known you for 15 years, but it's time to go.' He died painlessly and comfortably with the vet talking to him the whole time. It left such an impression on me," Mr Rosendorff said of the death he witnessed as a teenager.

The 58-year-old, who has just months or possibly weeks to live, wonders why he is not able to die as peacefully.

Letters in The Age:

WHEN my youngest brother was dying six years ago at the same age and with a similar cancer as Alan Rosendorff (The Age, 1/7), he faced three great fears: his imminent and painful death; the death of his independence, his control, his persona, should he be put in care under palliation; and the influence of the Catholic Church, which claimed a form of ownership over his atheistic life and wished to prolong his misery to the last second.

He circumvented these horrors by ingesting Nembutal through the feeding tube implanted in his chest and died in good company quickly, peacefully and painlessly. As far as a death can be good, his was a good death. And it was good because of the drug he could not legally be given.

John Guest, CamberwellALAN Rosendorff, you have my wholehearted support and sympathy. Two months ago my dear, brave mother died. She was constantly vomiting and in excruciating pain. Palliative care was not provided until she had suffered for far too long and she died the day that it commenced. People who so choose should be allowed to die with dignity.

Maureen Kutner, Glen Waverley

PROFESSOR John Ozolins (Letters, 2/7), the article about Alan Rosendorff (The Age, 1/7) did not imply that opponents of voluntary euthanasia are against a painless, comfortable death. And proponents do not seek ''to introduce the deliberate killing of human beings''.

We recognise that palliative care may have its limitations for some sufferers, who in carefully controlled circumstances should be granted medical help to end their lives at a time and in a place that feels right for them. We respect the views of those who believe this would be a violation of their religious beliefs. We just ask that they respect the views of suffering people who want the choice and those doctors and nurses who believe they should be allowed it. It is a cop-out for Premier Ted Baillieu to say that this is a federal matter. The relevant legislature is Victorian and the matter needs to be considered by the Victorian Law Reform Commission.

Anne Riddell, MelbournePROFESSOR Ozolins misses the point with regard to comparing human life to that of a dog. I took Alan Rosendorff's comment to mean that a dog is given more dignity in death than a human being.

Also, palliative care is a wonderful resource, but it is not perfect. From my experience with my father, there was some exemplary support and some very poor support in making his last days comfortable and pain-free. Unless palliative care can offer excellent care at all times, people should be allowed to plan how to end their lives.

Donna Jansz, CheltenhamTED Baillieu says he will not support pro-euthanasia legislation because it is too ''divisive''.

Survey results published by Dying with Dignity Victoria show that support for it has been steadily rising since the 1960s. In 2009, 85 per cent of respondents said they supported its legalisation. Only 10 per cent were opposed and the remaining 5 per cent were presumably undecided. It seems clear that the community made up its mind some time ago. It is the politicians who are lagging, too scared to show leadership.

Bronwyn Benn, BurwoodI HAVE the utmost sympathy for Alan Rosendorff. While we have governments that only listen to the Right to Life people, there is no hope for euthanasia to be the dignified and peaceful end to life for those suffering ghastly indignity.

My husband, who had motor neurone disease, would have chosen to have his life ended well before it did. After eight years of a long, slow and undignified disease for which there is no cure, I would have helped him do so. Those who say that life is sacred have no idea that it is not for those suffering pain, despite receiving excellent help from carers and palliative care nurses. It is the indignity of having catheters inserted and fouling the bed with faeces, etc. Euthanasia is dealt with well in many countries and it could be done well here. I urge politicians to be intelligent and compassionate and to act soon.

Kaye Cossar Stokes, KewWHY do MPs show compassion for the suffering of animals by suspending live cattle exports, yet allow humans to unnecessarily suffer by denying them access to euthanasia?

Harry Hauptmann, Mount ElizaEND of life decisions should be the business of patients and their doctors, not moralising busybodies.

Richard Moore, MelbourneBAILLIEU, head of our do-nothing government, passes the buck again, this time on euthanasia.

Ros Levy, Bentleigh East

THE Premier is mistaken if he believes physician-assisted dying is a federal matter. The law relating to hastening death or assisting suicide is the Victorian Crimes Act. It is this legislation that inhibits doctors when faced with discussing and acting on patients' choices at the end of life. The view of the community on this matter has been clearly and increasingly supportive of change for years.

The government can respond in three ways. First, legislate for amendments to the Crimes Act as is occurring in South Australia. Second, introduce legislation to specifically allow physician-assisted dying with safeguards, or third, refer the matter to the Law Reform Commission to allow an assessment of options, and an expert, independent report regarding legislative change. This was the process successfully followed by the Brumby government that led to abortion law reform. It is time, Premier, to deal with this. It is not going away. Let's get on with it.

Dr Rodney Syme, vice-president, Dying with Dignity Victoria, Toorak

A FORMER Northern Territory chief minister has described Premier Ted Baillieu's political stance on voluntary euthanasia as ''weak'' and unconstitutional.

Marshall Perron, who sponsored the short-lived voluntary euthanasia laws in the Northern Territory, criticised Mr Baillieu for rejecting a call for a report on voluntary euthanasia laws for Victoria, despite personally supporting the issue.

Melbourne lawyer Alan Rosendorff, who is dying of cancer, wrote to Mr Baillieu earlier this month calling for a Victorian Law Reform Commission report on the issue.

In response, Mr Baillieu described voluntary euthanasia as a ''divisive'' issue that Victoria had already rejected in Parliament in 2008. Mr Baillieu said he would instead wait for the federal government to act on voluntary euthanasia.

But Mr Perron said in a letter to Mr Baillieu on Friday that the Commonwealth did not have the constitutional authority to pass voluntary euthanasia laws for states. He urged Mr Baillieu to rethink his position on a law review.

''Your statement that voluntary euthanasia is 'divisive and should be tackled on a national level' is a weak excuse for inaction,'' Mr Perron said in his letter.

''In fact, it is quite outrageous that real people, experiencing real suffering, are ignored because politicians are preoccupied with hypothetical harm that has not materialised elsewhere.''

Mr Perron said the federal government had used its veto rights over the Northern Territory legislation, but did not have the same veto rights over state laws.

Constitutional law expert Professor Cheryl Saunders, of the Melbourne law school at Melbourne University, agreed it was unlikely that Federal Parliament would have the power to introduce voluntary euthanasia laws.

Mobile medical teams that can euthanise people in their own homes are being considered by the Dutch government. The teams of doctors and nurses would be sent out from a clinic following a referral from the patient's doctor.

The proposals were disclosed by Edith Schippers, the health minister, in a written answer to questions from Christian Union MPs. She said that mobile units "for patients who meet the criteria for euthanasia but whose doctors are unwilling to carry it out" was worthy of consideration.

"If the patient thinks it desirable, the doctor can refer him or her to a mobile team or clinic," the minister wrote.

In her written answer, Ms Schippers suggested that "extra expertise" could be summoned in complicated cases involving mental health problems or an inability to consent to euthanasia because of dementia.

Dutch advocacy groups want to expand the eligibility criteria for euthanasia as well as open facilities specifically for euthanasia along the pattern of the Dignitas centre in Switzerland.

Hundreds of foreigners have made the journey to Switzerland either to end their lives or to register with the clinic.

Phyllis Bowman, a pro-life campaigner in Britain, said the proposals amounted to a "campaign to speed up euthanasia and to make it cheaper by doing it at home instead of in institutions".

The Netherlands legalised euthanasia in 2001 in cases where patients are suffering unbearable pain due to illness with no hope of recovery.

Euthanasia is usually carried out by administering a strong sedative to put the patient in a coma, followed by a drug to stop breathing and cause death.

To qualify, patients must convince two doctors they are making an informed choice in the face of unbearable suffering.

Dutch medics have been accused of practising euthanasia on demand.

A total of 21 people diagnosed with early-stage dementia died with the help of their doctors last year, according to a 2010 report on euthanasia.

The figures showed another year-on-year rise in cases with about 2,700 people choosing death by injection compared to 2,636 the previous year.

A Dutch government spokesman said: "The greatest care has been taken to regulate care for patients who are suffering unbearably with no prospect of improvement. Euthanasia may only be carried out at the explicit request of the patient."

From Nation of Change:

Peter SingerDudley Clendinen, a writer and journalist, has amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a terminal degenerative illness. In The New York Times earlier this year, he wrote movingly both of his current enjoyment of his life, and of his plan to end it when, as he put it, “the music stops – when I can’t tie my bow tie, tell a funny story, walk my dog, talk with Whitney, kiss someone special, or tap out lines like this.”

A friend told Clendinen that he needed to buy a gun. In the United States, you can buy a gun and put a bullet through your brain without breaking any laws. But if you are a law-abiding person who is already too ill to buy a gun, or to use one, or if shooting yourself doesn’t strike you as a peaceful and dignified way to end your life, or if you just don’t want to leave a mess for others to clean up, what are you to do? You can’t ask someone else to shoot you, and, in most countries, if you tell your doctor that you have had enough, and that you would like his or her assistance in dying, you are asking your doctor to commit a crime.

Last month, an expert panel of the Royal Society of Canada, chaired by Udo Schüklenk, a professor of bioethics at Queens University, released a report on decision-making at the end of life. The report provides a strong argument for allowing doctors to help their patients to die, provided that the patients are competent and freely request such assistance.

The ethical basis of the panel’s argument is not so much the avoidance of unnecessary suffering in terminally ill patients, but rather the core value of individual autonomy or self-determination. “The manner of our dying,” the panel concludes, “reflects our sense of what is important just as much as do the other central decisions in our lives.” In a state that protects individual rights, therefore, deciding how to die ought to be recognized as such a right.

The report also offers an up-to-date review of how assistance by physicians in ending life is working in the “living laboratories” – the jurisdictions where it is legal. In Switzerland, as well as in the US states of Oregon, Washington, and Montana, the law now permits physicians, on request, to supply a terminally ill patient with a prescription for a drug that will bring about a peaceful death. In The Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg, doctors have the additional option of responding to the patient’s request by giving the patient a lethal injection.

The panel examined reports from each of these jurisdictions, with the exception of Montana (where legalization of assistance in dying occurred only in 2009, and reliable data are not yet available). In The Netherlands, voluntary euthanasia accounted for 1.7% of all deaths in 2005 – exactly the same level as in 1990. Moreover, the frequency of ending a patient’s life without an explicit request from the patient fell by half during the same period, from 0.8% to 0.4%.

Indeed, several surveys suggest that ending a patient’s life without an explicit request is much more common in other countries, where patients cannot lawfully ask a doctor to end their lives. In Belgium, although voluntary euthanasia rose from 1.1% of all deaths in 1998 to 1.9% in 2007, the frequency of ending a patient’s life without an explicit request fell from 3.2% to 1.8%. In Oregon, where the Death with Dignity Act has been in effect for 13 years, the annual number of physician-assisted deaths has yet to reach 100 per year, and the annual total in Washington is even lower.

The Canadian panel therefore concluded that there is strong evidence to rebut one of the greatest fears that opponents of voluntary euthanasia or physician-assisted dying often voice – that it is the first step down a slippery slope towards more widespread medical killing. The panel also found inadequate several other objections to legalization, and recommended that the law in Canada be changed to permit both physician-assisted suicide and voluntary euthanasia.

Surveys show that more than two-thirds of Canadians support legalization of voluntary euthanasia – a level that has held steady for several decades. So it is not surprising that the report received strong backing in the mainstream Canadian media. What is more puzzling is the cool response from the country’s political parties, none of which indicated a willingness to support law reform in this area.

There is a similar contrast between public opinion and political (in)action elsewhere, including the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and several continental European countries. Why, when it comes to dying, do democratic institutions so often fail to translate what people want into legislation?

I suspect that, above all, mainstream politicians fear religious institutions that oppose voluntary euthanasia, even though individual believers often do not follow their religious leaders’ views. Polls in various countries have shown that a majority of Roman Catholics, for example, support legalization of voluntary euthanasia. Even in strongly Catholic Poland, more people now support legalization than oppose it.

In any case, the religious beliefs of a minority should not deny individuals like Dudley Clendinen the right to end their lives in the manner of their own choosing.

ABOUT PETER SINGERPeter Singer is Professor of bioethics at Princeton University and Laureate Professor at the University of Melbourne. His books includePractical Ethics, The Expanding Circle, and The Life You Can Save

Article in the Sunday Age:

THE blue mortar and pestle had gathered dust on his mother's Welsh dresser, before he used it to crush a dozen morphine pills in her kitchen. The powdered drugs dyed the water murky brown in the glass he held to her lips. She smiled gently after drinking, holding his hand.

''You are a wonderful son,'' she said. But Sean Davison's decision to help his mother die exposed a fault-line that has since torn at his family - and sparked claims his own sister in Melbourne betrayed him to police.

Late last November, New Zealand's High Court sentenced Davison, whom the judge described as an ''exceptionally devoted and loving son'', to five months' home detention for ''counselling and procuring'' his mother's suicide. He spoke to The Sunday Age last week from his three-bedroom confines, about the death that has come to define his life.

''I've had enough, this is not life,'' his mother, Patricia, 85, had said repeatedly from her sickbed. Cancer had spread to her lungs, liver and brain. She half-joked for someone to throw her into Otago Harbour, which she could see from her home near Dunedin, on New Zealand's South Island.

Davison, who lives in South Africa, had come home to nurse her. Patricia - a former GP and psychiatrist who loved painting, dancing and cathedral music - was desperate to die, he says, but feared a failed overdose might leave her alive and brain damaged. She started a hunger strike, hoping to hasten her demise but was still alive 33 days later, on October 25, 2006. Her body was rotting, she could no longer hold a glass of water to take the morphine she had instructed her youngest child to stockpile.

''I always kept trying to keep her alive … I was her caregiver. I would read to her and put CDs on to make her life as enjoyable as possible. It was only after some agonising that I conceded I had no choice,'' says Davison, 50, his soft voice shuddering on Skype. ''I had doubts all the way leading up to that moment … If she had told me at that last minute, 'No, don't do it,' I would have been relieved.''

He is lean with wispy hair and a square jaw. His home and own family - his partner Raine Pan and their boys, Flynn, 3, and Finnian, 18 months - are far away in Cape Town. Davison, head of the forensic DNA laboratory at the University of West Cape, was ordered to serve detention in a friend's house in Dunedin. ''I don't regret what I did, I regret being in a situation where I had to do what I did,'' he says.

''Once I told her I was going to help her, she was so relieved. I helped her to drink, then we waited and talked and I held her hand, and we chatted about family things … I felt great relief when she died. I was happy. I hugged her. It was only the next morning I started to think about the ramifications of what I had done.''

Davison's memoir of that time, Before We Say Goodbye, published in June 2009, omitted his role in the death on the request of his publisher's lawyers. But by then an earlier draft, which detailed his mother's overdose, had been given to police. The incriminating manuscript was separately sent to a New Zealand newspaper anonymously in late June.

As in Australia, euthanasia is illegal in New Zealand - despite two parliamentary attempts to pass ''death with dignity'' laws. Davison was visiting friends in Dunedin in September 2010 when he was arrested and charged, initially with attempted murder. He recalls the moment an officer placed the damning manuscript in front of him - it was then he saw it was the same copy he had given his older sister, Mary, a gerontologist and consultant in cognitive dementia at the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

''I felt shock,'' he says now. ''My instant reaction was the police had taken it from her when they interviewed her. Subsequently I learnt she wasn't interviewed … and then it became very obvious.'' Mary had twice taken legal action to stop publication, arguing Davison's book was libellous and breached her family's privacy (some of her identifying details were removed subsequently).