The following article appeared in the Sunday Age on 2 August 2009:

MOST of the time, it seemed that Dr Miklos Somogyi, retired mechanical engineer, didn’t really need a body. He was happy enough to have a brain for thinking his complicated thoughts, and his fingers to do the typing.

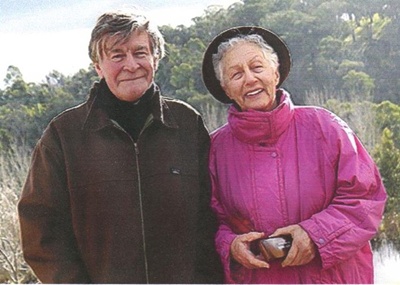

There was dining out at a local Italian restaurant or going to the movies with his wife, Erika, and for half an hour in the evening the world stopped still with the television news. But most of the action in Miklos Somogyi’s life took place in his sunlit study. ‘‘About 70 per cent of the time, that’s where he is,’’ says Erika.

For the past five years Somogyi has been working on a computer program that presents complicated mechanical components in 3D. The software is mostly complete. He needs another year to write the documentation so other engineers can make use of his baby.

‘‘And then, you know, I have another project. I have enough to do that would take me three lifetimes,’’ he says with the glee of a child with so many model aeroplanes to put together. Miklos Somogyi may not have the extra year he needs. There may be only six months left to him, or a couple of years. ‘‘It’s all so vague. No straight answers to my straight questions,’’ he says.

In July 2007, Somogyi woke up with intense back pain. Six weeks later, after a variety of scans and blood tests, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer, and with a secondary tumour that showed up as a tiny dot on the spine in a full-body bone scan.

A locum urologist gave him the worst news in a roundabout way. ‘‘He said it would respond well to palliative care,’’ he says. ‘‘He asked if we knew what palliative care was — he didn’t have to explain it to me.’’

Somogyi’s regular urologist mentioned ‘‘something about three years. Whether that was a painless existence or my life expectancy, it wasn’t clear at all.’’

A biopsy confirmed the diagnosis, and Somogyi was put on medication to help him cope. ‘‘The pain was gone, but at a huge price: I became a zombie. No energy whatsoever. My wife had to put on the leash to take me for a 100-metre walk.’’

And yet, for 10 minutes a day, Somogyi managed to crawl to the computer and work on his project. He also continued his long-time habit of writing letters to the newspapers.

‘‘He’s always written things down,’’ says Erika. ‘‘He likes to document everything. It’s what makes him happy. And this has been an extraordinary experience. It was more for him that he wrote it all down, and perhaps maybe for other people to know what is going on and what it is like.’’

About two months ago, writing in a haze of pain and rage from his hospital bed, unsure whether or not he’d walk again, Somogyi sent his 7000-word account to The Sunday Age. It presents a very raw portrait of a man coming to terms not only with death but with the madness of physical agony, the ‘‘panic and resentment that can pull families apart’’ when faced with the complexities of serious illness, the month-long despair of mistakenly believing himself to be a paraplegic with no light at the end of the tunnel, the horror of ‘‘becoming a vegetable’’, and the absurdity of a hospital system so large and impersonal that ‘‘you feel like you are being processed in a factory’’.

This was Somogyi’s rugged introduction to palliative care, where he found ‘‘a life that is no life’’.

‘‘And I know I will most likely go through it again. The cancer will come back and the next time there won’t be any coming home to Erika. It will be a nursing home — unless I do something horrible.’’

Like what? ‘‘Throwing myself in front of a car. A train. Plenty of people do it,’’ he says. This was Miklos Somogyi speaking to me at his home, where for the past month he has been finding new ways to define a good life: the hard-work joy of shuffling around on a walking frame; toileting with privacy; traversing the 20 steps up to his East Toorak flat by gripping the handrail like a rope on a mountain face. Recently he managed 15 metres walking on his own, with his wife in front of him, ready to catch him with the walker. These people are in their early 70s, and their life together has taken on the highs and lows of dangerous adventure. The first 18 months of Somogyi’s illness were spent at home, heavily sedated, keeping his project alive in dribs and drabs. It was in the new year when, as Somogyi writes, the pain returned.

‘‘I received five radiation treatments at The Alfred. In a few days the pain was gone and I was a perfect zombie again, sleeping 12 hours or more, doing nothing useful. But the complex regime of medication had many other side effects. Hot flushes with lots of sweating. I was itching with rashes. I was losing my hair. I lost the sense of taste. My speech was hoarse and too loud because I couldn’t hear myself because my hearing was affected.’’

After three weeks of this, there was a temporary miracle. An anti-inflammatory medication had the effect of an amphetamine on Somogyi’s system, and he found himself sprinting around the apartment. ‘‘Usually I woke up at 11 or so, and slept a lot in the afternoon. Now I found myself in the study at 7am … I accomplished more in a few hours than what the zombie did in weeks. Have you ever seen a 72-year-old hyperactive kid? I got my life back.’’

The manic revival lasted a week, and the comedown was brutal: an invasion of pain that reduced him to a panicked and demented raging. ‘‘Our doctor sent us to the emergency [department] of The Alfred. First we went home to collect a few things in haste. In agony I was shouting about the smallest things that Erika, understandably, took in a bad way. I was saying a lot of things that were completely out of character. We have been married more than 20 years, and never a loud argument, just love, even when we disagreed.’’

On the drive to the hospital, every change of gear, every step on the brake brought another hell-soaked scream. ‘‘We arrived to The Alfred and I was beside myself. I remember Erika complaining that I was aggressive, and a male voice kept asking me questions that I did not understand.

I remember shouting that I was in pain. In the haze I did not notice that Erika was in deep panic, that she was trembling all the time. I brought up old things that made her scream.

Thank God that the damage I caused was overridden by love but it took weeks before the trembling ended. An episode like this might have torn apart a weaker family.’’

Somogyi was admitted to The Alfred at the end of January. When he later tried to document his first weeks, he couldn’t decide whether various episodes ‘‘were real or just my imagination’’.

It is necessary to point out here that Somogyi wasn’t experiencing actual palliative care, beyond the numbing drugs. In a hospice, the nursing has an inherent pastoral component as well a practical one. Palliative care is a specialist field where there is a strong awareness that a ‘‘difficult patient’’ is more often than not a patient in physical and emotional distress. At The Alfred, Somogyi was just one of many people who needed to be made well enough to send elsewhere. Too often it seemed that the hospital workers regarded him as a difficult patient, with no understanding of his fragility.

He writes: ‘‘It was necessary to have some CAT and MRI tests. A few young guys wheeled patients down to the basement to the machinery. They ran on the corridors, used the brakes, accelerated like a Schumacher, and were perplexed that I was shouting: a finicky customer. They weren’t told about spinal cord damage and related pain. From now on I was full of fear, and they were full of resentment when I complained, and then handled me without the slightest regard for my condition.

‘‘During another MRI scan I was wrestling with someone and heard a female voice: ‘He hit me.’ Whether it was haze or real, I’ll never know. Anyway, if a patient causes some trouble, then his reputation will follow him/her quite a way up.’’

In the first week especially, it seemed that Somogyi was caught in a permanent state of emergency. And to a large degree this was true. He needed surgery to rescue his spinal cord from annihilation.

He writes: ‘‘One day many experts from radiology and neurosurgery gathered to discuss my case. They offered me surgery to remove [the tumours] where there was no danger that the cancer would further spread, and put in some nuts and bolts to strengthen the spine.

‘‘They explained all the dangers but they added that these risks are not high and they gave me a piece of paper to sign if I agreed. Full of trust, I signed. The operation took place a few days later. A massive nine-hour operation: huge wounds on my back. When I woke up, I was told I had lost the use of my right leg, except the toes.

‘‘Never, ever sign a paper as stupidly as I did. The offer must be in writing well before the operation, leaving time for the whole family to digest it and get a second opinion, so that you can give an informed consent.’’

It was Erika who told him he was virtually paraplegic. With no one at the hospital telling him otherwise, Somogyi began wishing the rest of him would die too. He writes: ‘‘It took me a few days for the facts to sink in. I was a cripple. I will not be able to walk. I’ll be in a wheelchair. If I drop something, I have to wait for somebody to pick it up for me. I won’t be able to go up/down stairs, so I will be confined to a small area. No going out to a restaurant or a movie. And, most of all, how shall I get to the toilet and shower?

‘‘For the last question I got an answer rather soon. First, still in bed, a brace was put on me to prevent my spine buckling. It dug into my chin and sides, and pressed my spine if it was not correctly applied. Then, with help, I sat on the side of the bed. Someone wheeled in a huge lifting machine. I was attached to it, the machine then transferred me onto a commode. I was untied from the hoist and wheeled above the toilet.

‘‘When ready, someone wiped my botty and wheeled me into the shower. All this required two nurses, and was a blow to my dignity. How would I do this at home? And where would we have enough room for such machinery? Or shall we sell our cherished home to be able to get into a nursing home? I wished that I could just expire somehow. Voluntary euthanasia was high on my mind.’’

It wasn’t until a month later, when he was moved to Caulfield Rehabilitation Hospital, that a number of muscles were found to be working in Somogyi’s leg. He was told that physiotherapy might give him back a life worth living. On the other hand, at a family meeting to discuss his future, he was warned that the chances of him walking again were small. Reluctantly, Erika began checking out nursing homes. ‘‘I wanted him at home but we had to look at the option. I found we couldn’t afford the $300,000 they wanted for a bond,’’ she says.

Meanwhile, Somogyi’s wasn’t able to start physiotherapy straight away because he’d come down with shingles and he was put in quarantine.

‘‘Even during this quarantine,’’ he writes, ‘‘I was transferred daily for a radiation treatment — the last 10 sessions. I don’t know whether it was due to radiation or not, my tastebuds were reprogrammed and I found most food, and even water, revolting. … By now I [had] lost some 25 kilos and my muscles and strength were gone.’’

MEANWHILE, a clot was found in his lung. And then one of the rods came loose from his spine, and he needed another operation back at The Alfred. The glimmer of hope took on a taunting, impossible quality. Exhausted, Somogyi fell into despair.

‘‘I was in the deepest point in my life, at the end of my tether. I cancelled the remaining five radiation sessions. I told the gathering of doctors that I did not want to live this aimless life that will inevitably end in another hospitalisation and to please respect my wish. Of course, they could not. Of course they saw my potential much better than I did. Today I agree with them … wonderful psychiatrists consulted me, never contradicting me, and I felt their full sympathy all the time. They prescribed some calming medicine that ended my nightmares.’’ It was at this emotional turning point that Somogyi — fuelled by anger and a sense of purpose — found his pluck and started writing, with a laptop sitting above him on the swing-away table. And when he finally started physio, a gruelling program in which he was training to go home, the writing took on a joyful colour.

‘‘When I could move my bad leg … Erika cried. We started practising ‘transfers’, from the edge of the bed to a wheelchair and back. This gave me the opportunity to get out of bed and whizz around, in the brace, of course. First we did the transfers with the help of a sliding board. Later I could stand on my feet unsupported for some two minutes … Next was from bed to the commode and back. This made the lifting device redundant. Holy cow, this was great! Going to the toilet and shower no longer needed two nurses … Freedom!’’

As much as she was excited her husband was coming home, Erika Somogyi had doubts about how she would cope. ‘‘But we are managing very well … it’s good for me to know I don’t have to worry.’’

The physio sessions are continuing at home and a carer comes three times a week to help Somogyi in the shower. ‘‘Miklos keeps saying he is confident about going it alone.’’ And while Somogyi pushes himself, testing the limits of his freedom, willing himself to get around without the walking frame, much of his time is spent on the computer. There’s the software project to complete, but also letters to write.

Last year, in his zombie state, Somogyi wrote to Premier John Brumby: ‘‘It happened many years ago, but the picture of my father as a 30-40 kilo skin-and-bone mass of agonising pain still haunts me from time to time … Now I am diagnosed with inoperable cancer of the spine … I have a good idea of what’s in store for me, and I do not wish to die the way my father did. But what options do I have? Kitchen knife, gas, driving into a train? Mr Brumby, I really don’t want to kill myself. I only want an insurance policy, just in case. If I can’t have that, I need to do something horrible …’’

Somogyi pleaded with Brumby to support the Medical Treatment (Physician Assisted Dying) Bill 2008. The Premier didn’t comply. The bill was predictably defeated in the upper house last November. Brumby no doubt receives countless letters like the one he received from Dr Somogyi. Voluntary euthanasia is off the agenda as far as the State or Federal Government is concerned, but it gnaws away at our ageing society. In the past two years, there were 179 newspaper articles published in Australia that dealt with euthanasia.

In the preface to his hospital-bed journal, Somogyi rails: ‘‘The politicians argue … there’s no need to discuss voluntary euthanasia. But their enthusiasm for palliative care as ‘the’ solution to all problems is misleading at best, and a deliberate lie at worst.’’

Now, at home in his study, swivelling in his wheelchair to face me, with wet eyes and shaking voice, he suddenly becomes very calm and steady. He is, after all, a veteran problem-solver. When he says he’ll figure out an ‘‘exit strategy and avoid ending up as a vegetable’’, I believe him.

After three weeks at home, Miklos Somogyi was re-admitted to the Alfred with intense back pain. The cause is being investigated.

THE FOLLOWING LETTERS APPEARED IN THE SUNDAY AGE ON 9 AUGUST 2009 ABOUT THE ABOVE ARTICLE AND ISSUES OF EUTHANASIA

I'D LIKE to make comment about John Elder's article ''The unbearable agony of being'' (2/8). I will eventually face death from prostate cancer down the road of life.

I have given a lot of thought to how I am going to have to extinguish my own life as we here in Australia have no medically assisted death legislation. I find it unfathomably unbelievable that a terminally ill person does not have any rights to his/her own passing.

I know what I am going to do to end my life when I feel that I've had enough. I just hope that it works. My greatest fear is that something will happen to me, such as having a stroke, which will make it impossible for me to act and (so I'll be) stuck with palliative care.

The parliamentarians who didn't support the doctor-assisted death legislation should be forced to wander through the cancer wards, which hold prisoner the terminally ill.

I find this whole palliative care issue most disturbing and find that all it does is prolong the agony of it all.

SUMNER BERG, BeechworthCONGRATULATIONS on publishing the moving story of Dr Miklos Somogyi. I wish to express my concern that this is one case where palliative care cannot control the patient's pain. Legalised euthanasia must become law in Australia.

Having spent a lifetime in the Victorian police force witnessing the results of numerous suicides committed in horrible ways by those suffering intolerable pain, I support appropriate legislation to correct this anomaly.

GEOFF TULLOCH, ElthamTHE article by John Elder on the ordeal suffered by Dr Miklos Somogyi once again raises the topic of the refusal of our governments state and federal to legislate to allow people suffering from terminal illness to seek medical advice to enable them to maintain control over the final stage of their lives, and to die with dignity. Palliative care is as good as it can be with current knowledge and resources, but cannot ease the pain and distress suffered by some, such as Dr Somogyi. Politicians will only take action for change if enough voters voice their reasons for wanting change. I simply want to add one more voice to the growing number who consider that the time is overdue for a properly constructed and supervised Right to Die act to be passed.

JEREMY BARRETT, MalmsburyYOUR article shows how unfair it is for politicians to play God and decide to take away, from an obviously intelligent and rational person, the decision to end one's life. It's really nobody else's business, but their own.

DIETMAR BRISKER, HuntingdaleAS A community we are rightly outraged when two irresponsible radio presenters rob a young girl of her dignity. Indeed few events in recent memory have caused such strongly worded responses both in opinion pieces and in letters to the editor. Yet in this case the issue of consent is problematic since the girl's mother actively participated.

The community has also registered strong repugnance about other practices that rob people of their dignity and humanity - the treatment of refugees and the treatment of suspected terrorists, for example. A community that fails to recognise the inherent worth of each person and to respect their dignity is a community that is morally debased.

The examples may be extended to that reported in ''The unbearable agony of being''. This case also presents a picture of an individual robbed of his dignity. Loss of dignity and humanity is forced on to many individuals because our state politicians failed to pass rational laws with regard to euthanasia. And here there is no equivocation about consent.

Many people want physician-assisted dying as an option in their end of life choices and 80 per cent of the community supports them in this wish. Members of the Victorian Parliament, to their shame, defied public opinion and moral rationality in this matter and have condemned many to a grave loss of dignity at the end of their lives. It is a matter that should be promptly referred to the Victorian Law Reform Commission.

RALPH BLUNDEN, HawthornJOHN Elder's story affected me - in part because I'm 80.

Last month I discovered that back in 1936, when he was aged 71, King George V was very ill with lung problems. His doctor, Lord Dawson of Penn, without medical consultation or approval from Queen Mary or the future kings Edward VIII and George VI, decided to assist him in dying by injecting a lethal dose of morphine and cocaine. This only became public in 1986 when, after 50 years, Dawson's diary was opened. Dawson said his action was ''a facet of euthanasia or so-called mercy killing''.

Had I known from the age of seven to 57 that my king had been lethally injected by his physician I'm sure that I would not have waited until now, when I can expect health problems - hopefully not as severe as Miklos' - to support any future legislation allowing for a dignified death.

KEN NEWTON, NunawadingMIKLOS Somogyi is far from the only dying person to have written to the Premier in support of the Physician Assisted Dying (PAD) bill. The Premier claimed the matter was one for MPs' consciences. However, when PAD could have been referred to a committee for public comment (and 80 per cent of the public support it), he forced his party to vote as a bloc to prevent this. With the abortion bill, John Brumby protected the rights of women to control their bodies. He should do the same for the dying.

JANINE TRUTER, The Basin

THE FOLLOWING LETTERS APPEARED IN THE SUNDAY AGE ON 16 AUGUST 2009 AND THE AGE ON 17 AUGUST 2009 ABOUT THE ABOVE ARTICLE AND ISSUES OF EUTHANASIA

Sunday Age letter 16 August 2009MY YOUNG brother died in a cancer ward 14 years ago. I considered holding a pillow over him in a ward at Peter Mac. I didn't because I feared his beautiful eyes would open and look at me. He lived four more weeks at home and at Frankston Hospital. He had time to mend fences, console his children and his courage was monumental; he died peacefully, his pain was managed, I will never forget his dignity.

Just before Christmas last year, my oldest brother died of cancer. He had endured four years of his illness and, at times, looked like he might survive it. He played nine holes of golf weekly, and danced with the RSL ladies on Friday nights; the ladies poked his oxygen tube back in when the dance became wild.

When my turn comes, the example of the courage of both my brothers will shame me into imitation of them. It is a slippery slope before our feet, expecting doctors to be vets.

KERRIN HARVEY, WonthaggiI AM elated that common sense has prevailed in the Christian Rossiter case (''Court upholds quadriplegic's right to starve to death'', The Age, 15/8), and that he has been granted the right to choose his own path in life, even if that choice leads to his death. We have been cautioned not to relate that judicial decision to the wider question of voluntary euthanasia, yet it must at the very least be seen as a glimmer of common sense through the darkness of fear and ignorance.

Surveys consistently reaffirm vast community support for controlled euthanasia, and our belief in the right to make our own life choices. Eventually sanity must prevail and ultimately politicians must act on behalf of that huge majority.

I hope that I shall live to see such political courage emerge, and that I shall not have to slink off furtively to a more enlightened land to end my days. Our politicians have a duty and an obligation to act upon the wishes of the electorate, rather than acquiesce to a fearful minority and their own selfish political conservatism. Who among them has the courage of our convictions?

Bob Thomas, Blackburn SouthA COURT rules that an aged-care centre in Perth will not be breaking any law if it assists a quadriplegic man to voluntarily terminate his suffering through starvation. Yet if someone offered this same gentleman some Nembutal, the drug of choice to terminate a life far more quickly, painlessly and peacefully than the primeval process of starvation, they would be charged with assisting a suicide and possibly jailed. Is it just me or is it society in general that is losing the plot?

Malcolm Chalmers, Newtown, NSWCHRISTIAN Rossiter was successful in the Western Australian Supreme Court in confirming his right to refuse medical procedures. The right-to-life people tell us they are considering an appeal. Presumably they are asserting that their god gives them a right to interfere in people's court cases?

Roy Arnott, ReservoirREFUSING food and drink is really an awful way to die. It could take a few days or weeks to die of starvation and dehydration. Hopefully, Christian Rossiter can have good palliative care, with increasing doses of morphine and sedatives. This is commonly known as ''terminal sedation''. It is much more dignified and not so drawn out.

Perhaps in Victoria the whole matter of euthanasia and the Medical Treatment Act of 1988 should be referred to the Law Reform Commission for review?

Mike Tinsley, KewMR ROSSITER has no real quality of life. Giving him an extra dose of morphine is considered murder, but to watch him starve himself to death is OK. Animals in similar situations are treated with more compassion and kindness to end their suffering.

Marie Nash, DoncasterChristian Rossiter (a human) has to slowly and painfully starve to death, while Sam (a koala) is mercifully euthanized.

Bill Pell, EmeraldMay it be peaceful, Christian Rossiter. Thanks for pushing the boundaries.

Anne Rogan, GreensboroughThe law allows the hopelessly ill to die over several days through starvation, while a quick and dignified exit with drugs is forbidden. How compassionate we are.

Marshall Perron, Buderim, Qld.

This article is from The Age newspaper:

Let me paint a picture. It is my mother's 91st birthday. She lives in an aged-care facility. When we were kids it was called a nursing home. It is a beautiful building surrounded by gardens and staffed by genuinely kind people who take great care of my mother.

She has broken both her hips and her pelvis in the past decade, as well as going blind from macular degeneration. She has not recognised or responded to her children for more than a year; her dementia started more than 15 years ago. She has been in dementia specific care for 10 years and high care for five years.

She is always asleep when I visit. Mouth open, snoring slightly, front teeth no longer protruding. Both her parents died before she could get braces for her teeth and they always protruded slightly. She was very proud of her teeth and she looked after them until she developed Alzheimer's. Now they are broken and have apparently disintegrated, but it is of no concern because she no longer needs them to chew her food. She is fed a protein enriched puree, which she swallows, as no doubt she did when she was an infant.

Let me paint another picture. I am 12 years old. My grandmother has been brought out from her nursing home to visit the family. She is a beautiful 83-year-old. She had been an intelligent woman who had many talents from painting to woodwork to writing poetry. She is credited with suggesting when she was a young woman that a white line be painted down the centre of the road from Gosford to Sydney.

As she aged she developed dementia. She also had glaucoma, which was controlled with drops. A symptom of the glaucoma was seeing flashing lights. She would ask us to go to a certain spot in the room because she thought there was a fire there, and we had to put out the fire by stomping our feet.

This was a great joke for a while, but she gradually became blind and no longer saw her little fires. My mother's response was to repeat what became an often-heard request. ''If I ever get like that I want you to put a pillow over my head.''

Last month, a 70-year-old Englishman was arrested for doing just that to someone he loved. He admitted putting a pillow over the head of his partner who was in ''terrible, terrible pain'' and smothering him in the 1980s.

Author Terry Pratchett, who has Alzheimer's disease, has suggested the possibility of special panels being created to allow seriously ill people to argue their right to die legally.

In Australia, we do not have euthanasia as a legal option, but it was my mother's strongest desire to die rather than live in the vegetative state in which she now lives. My father promoted influenza as the remedy for old age, but even if she were to contact influenza, antibiotics would be administered and her life would continue - a life empty of all that we take for granted and a life my mother would scorn if she could speak.

Exploitation of the elderly and greedy children who cannot wait for their inheritance are put up as arguments against euthanasia.

When my sister was on life support after an aneurism more than 30 years ago, a system was in place so that her life support could be turned off after a panel of doctors pronounced her ''brain dead''.

Why can't a similar system work for those people who wish to die with dignity either because of extreme pain due to terminal illness or who put in place a wish to die when they no longer recognise their family or communicate or experience life as we know it?

My mother never wanted to be a burden to her family or live a life devoid of meaning. She would be horrified if she knew the distress her children felt because of her condition.

The problem today is that there are too many opinions as to what is right. The religious do not approve of abortions or euthanasia, but not all of us want to live by their guidelines. The politicians have to please the people they think will vote for them.

Until euthanasia is legal, we are denied the right to make a choice. I do not wish to follow in my mother's footsteps, and make a definite plea that if I succumb to dementia I want some kind soul to enable me to go peacefully. Or, failing that, to put a pillow over my head.

Belinda Ramsay is a Melbourne writer.

Letter in The Age newspaper:

BELINDA Ramsay (Comment, 25/3) points out the profound indignities that people may face in a prolonged and agonising dying process, despite the best care. What many Victorians don't know is they can help protect their rights by completing several documents, including appointing an agent to make legally binding treatment (or refusal) decisions on their behalf when they are unable to participate in decision-making.

Advance Healthcare Directives are also very important. AHD forms allow anyone in a state of sound mind to stipulate what medical interventions they would want to receive, or to refuse, in particular circumstances such as the result of a stroke, a serious car accident, or advancing dementia.

A collection of the forms is available free from the website of the non-profit Dying With Dignity Victoria. We urge every Victorian to consider carefully and document what they believe would be a dignified conclusion to their life in regard to medical treatment before it's too late. Otherwise, decisions could be made that are out of line with one's views and values.

Neil Francis, Dying With Dignity Victoria, Melbourne

The following news report was in The Age newspaper:

A MELBOURNE cancer patient who imported the euthanasia drug Nembutal has avoided conviction after a court heard she was motivated only to relieve the suffering of others.

Her barrister described Ann Leith, 61, of Camberwell, as an outstanding person and selfless community contributor for many years who had been moved by witnessing the elderly in pain.

Barrister Geoffrey Steward said what differentiated her circumstances from others who pled guilty to offences was that her ''sole motivation for the commission of the offence was born as a result of her kindness, humanitarianism and a desire to potentially relieve the suffering of a fellow human being''.

He said Leith committed the offence after regularly attending Exit International meetings where she saw aged and infirm people in pain who were unable to know what to do to alleviate their suffering.

In placing her on a $500, one-year bond, magistrate John Lesser said while individual views were respected, ''when the law is in play against them, the law wins out. If you offend again, the courts will treat you much more harshly.''

Leith was stopped at Customs at Melbourne Airport last March with two perfume bottles later confirmed to contain Nembutal with a purity of 5.32 per cent. She was believed to be the first Australian to be charged with importing the border-controlled drug.

When police searched her home a month later, Leith was candid and honest, said Mr Steward, and told them her motivation.

Prosecutor Mario Camilleri said Leith told police she imported the drug to help others in a similar situation to herself. She had previously imported the drug for herself and her husband, both in remission for breast and bowel cancer respectively, and had stored it ''for a rainy day''.

Mr Steward said that Leith did not want to turn the case into a cause celebre, and unlike the prosecution, which suggested she might reoffend, her admissions, guilty plea as well as her acknowledgement of wrongdoing was an acceptance of a ''dichotomy between the law and her philosophical views and she acknowledges and accepts the law must take precedence''.

Mr Lesser told her: ''The notion of importing anything for other people has serious implications for the community. What you do in relation to yourself and your husband is another matter.''

He also ordered her to pay $1000 to the court fund and ordered $137.70 of costs against her.

Exit International founder Dr Phillip Nitschke said the sentence was ''a victory for common sense''. ''This shows an understanding judgment on the part of the magistrate,'' he said.

One of my favourite people is an old boyfriend's mum, Marijke, a stuttering Dutch psychologist, heart of gold, body of a Veronica and a penchant for buying old furniture, painting it beige and re-upholstering it in calico.

Meeting her in my teens was a revelation. The women I knew mostly fell into the category of teacher, housewife, mother, nurse or tuckshop lady rather than fiercely independent, free-thinking European woman who cooked lentils, travelled the world and danced to her own tune. Clothes optional.

I caught up with Marijke a while ago to meet her new man, Rene, a Dutch cardiologist. The little boys and I rolled up to a breakfast by the sea. Whole-wheat pancakes, bowls of stewed fruit the colour of jewels, fluffy clouds of yoghurt, steaming cups of coffee and light streaming in. At the moment I was reflecting on what a healthy sight it was, Rene pushed his chair back and lit a cigar. At the table.

I love Europeans.

He turned to me and said: ''Cathy, did Marijke tell you how we met?''

''No, she didn't.''

He took a drag of his cigar and said: ''I killed her father.''

Rene had legally euthanised Marijke's father in the Netherlands, where euthanasia is legal. A death with a happy ending.

I thought of Marijke and Rene when I addressed the Dying With Dignity Rally on the steps of Parliament House last week.

Passionate supporters huddled together on the steps like many Melburnians past. I hoped this was the last rally for euthanasia ever, but infuriatingly I knew it wouldn't be. Despite the need for our laws to catch up to reflect social progress and our community values, 85 per cent of people support voluntary euthanasia.

I was disappointed by the turnout - about 150 people. Some 10,000 rocked up to the Save Live Australian Music Rally when they closed The Tote. But the collective age at the Dying With Dignity Rally was probably twice that of the Slam Rally. Perhaps it's a good sign - maybe people were thinking: ''I don't have to turn up to a rally for voluntary euthanasia. Clearly it's going to happen; they legalised abortion.''

WAKE UP everybody! Politicians know 85 per cent of us want euthanasia. BUT WE DON'T HAVE IT! Shirtfront your local member and say: ''Pull your finger out, sunshine, and speak up. Because you're just The Honourable Member For People Dying in Pain.''

Dogs can be legally and peacefully put to sleep, (sure, many of them we're more fond of than our relatives). Other countries safely administer voluntary euthanasia, so don't give me any bull about it being dangerous or us not being responsible. We all know doctors, thanks to the benign conspiracy between the legal system, the police and the Victorian government, euthanise people every day.

So why is it illegal? Blame religion. Yet 85 per cent of people support euthanasia, while only 9 per cent of people go to church. The majority of people with faith believe in voluntary euthanasia.

I don't care what you believe, but we all must fight for a secular state to stop religion influencing our policy. And I don't care who you vote for, if you believe that Jesus was sent to Earth to die for our sins, clearly Tony Abbott was sent to Earth to live for our sins. Not having access to voluntary euthanasia is an infringement of our rights. Article Five of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: ''No one shall be subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.'' I would proudly, safely, euthanise a loved one who needed it. And happily be fined, prosecuted or incarcerated as a result.

Turn up to the next euthanasia rally. Because there are people lying in hospital, at home and in palliative care who would streak down Bourke Street to shake up this mediaeval mentality of a few. Otherwise we may all have to become veterinarians so we have access to Nembutal.

''What do we want? To die. When do we want it? When we choose.''

That's me, attempting to sex up euthanasia. Everyone deserves a happy ending. Not just Marijke and Rene.

Catherine Deveny’s one woman show God Is Bullshit has been extended due to popular demand.For more details go to www.catherinedeveny.com Her column (Editor's Note:NO LONGER!!!) appears in The Age's MelbourneLife on Wednesday.

FOOTNOTE: THE AGE SACKED CATHERINE DEVENY FOR WHAT THEY SAW AS A PUBLIC MISDEMEANOUR WHEN ALL SHE WAS DOING WAS TO TELL IT LIKE IT IS!!

A terminally-ill woman and her husband found dead in their home near Perth had contacted Dr Philip Nitschke's assisted suicide group three years ago, the right-to-die campaigner says.

The bodies of Jennifer Anne Stewart, 61 and her 66-year-old husband John were discovered on Monday by a family member in their home in Sawyer's Valley, 40km east of Perth.

Ms Stewart was terminally ill with cancer and it is believed she and her husband made a suicide pact.

Dr Nitschke said the couple had contacted the organisation he founded, Exit International, in February 2007 to seek information.

The organisation provides information and advocacy on assisted suicide and voluntary euthanasia.

Dr Nitschke said the situation demonstrated a need for legislation which would allow terminally ill people the right to die and provide legal immunity to anyone who assisted.

"We've got a situation here of a person who's seriously ill, in fact close to death, who effectively needs assistance to end their life," he told AAP on Wednesday.

"For what I know of the issue, in Western Australia the person who provided that assistance would be looking at seriously legal penalties including life imprisonment."

Dr Nitschke said there were accounts that Mr Stewart chose to end his own life through fear of the legal consequences he would face in assisting his wife to die.

He said the length of time between the couple's contact with the organisation and their apparent suicide demonstrated the Stewarts had made a rational decision.

"This should be quite reassuring that when people seek information, they take a lot of time to consider all their options," Dr Nitschke said.

"I'm sure the Stewarts considered all their options and then decided to take a path like this. "I don't think we should be getting too distressed that this happened."

WA Police said investigations continued into the deaths and whether there was any involvement of Mr Stewart in his wife's death.

An autopsy on the bodies is expected to be undertaken on Wednesday and police will prepare a report for the coroner.

* Readers seeking support and information about suicide prevention can contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or SANE Helpline on 1800 18 SANE (7263).

From The Age newspaper:

DETECTIVES raided Exit International's Melbourne offices yesterday, sparking outrage from the pro-euthanasia group.

Police served a search warrant at the Exit International offices at Doncaster in relation to the death of a South Yarra woman on May 8.

Exit International director Philip Nitschke said the raid was uncalled for and the voluntary euthanasia group would have given police any documents they required.

Dr Nitschke said the documents served were in relation to ''aiding a suicide'' and had been signed by homicide detective Senior Sergeant Ron Iddles.

The woman concerned was in her 60s and is believed to have been terminally ill. ''When a person does end their life, police feel that they need to investigate, to see if somebody has assisted,'' Dr Nitschke said.

He said it was the second time the group's Melbourne offices had been raided. Police had also been to Exit offices in New South Wales, Queensland and Darwin.

''There have never been any charges laid. We are getting a bit fed up with this,'' he said.

''This is not the first time the police have arrived at our [Melbourne] office out of the blue. The same happened in November 2009 over the suicide of another Exit member. ''The police should bear in mind, Exit is not some clandestine organisation that operates underground.''

Senior Constable Jo Stafford said police had taken great care to ensure all protocols were met yesterday and had handled the matter with as much sensitivity as possible.

''It is a sensitive issue when you are dealing with a person's medical records, but we have standard procedures to follow,'' she said.

Dr Nitschke said: ''It is totally unnecessary for the police to pounce on our office unannounced. In reality, they need only pick up the phone if they wish us to provide details about a deceased member of our organisation.''

Exit International has been connected to high-profile euthanasia cases around the world. In 2005, police launched an investigation into its involvement with terminally ill Point Lonsdale man Steve Guest, 58, who was advised by Dr Nitschke on ways to die.

Mr Guest, who had oesophageal cancer, made a public appeal for a ''peaceful pill'' to end his suffering.

He died at his Point Lonsdale home in July 2005, from an overdose of barbiturates.

For help or information call Suicide Helpline Victoria on 1300 651 251, or Lifeline on 131 114.

This article was in The Age on 13 September 2010:

A still from the pro-euthanasia television advertisement. Dr Nitschke said he would try again with a different version of the TV ad. Photo: Stephen Curtis, Seven News

A CONTROVERSIAL pro-euthanasia television advertisement, due to air last night, has been banned.

The ad's creator, lobby group Exit International, says the ban is a violation of free speech and it will try a different version within days.

The ad, which can be seen online, has an actor playing an ill-looking man sitting on a bed in his pyjamas.

He reflects on the choices he has made throughout his life, then says he did not choose to be terminally ill.

''I didn't choose to starve to death because eating is like swallowing razor blades,'' he says in the ad.

''I've made my final choice. I just need the government to listen.''

Free TV Australia, which regulates the industry, withdrew its permission for the $30,000 ad to be screened on the grounds it promotes suicide.

Exit International founder Philip Nitschke said the right to free speech and to lobby for legislative change was threatened by the ban.

''In an open democratic society, it's very important to be able to advocate openly for law reform,'' Dr Nitschke said.

''They've effectively curtailed any open discussion of political change on this important social area.''

Dr Nitschke said he would try again with a different version of the TV ad on Monday.

Exit International will also press ahead with plans for a billboard version in Sydney, and will try to screen the TV ad in New Zealand.

Dr Nitschke said it would have been Exit International's first TV ad.

It was to have aired on Channel Seven.

He said the actor was not terminally ill because to use an ill person may have seemed exploitative.

Euthanasia is not legal in Australia. State laws prohibit anyone from assisting or giving advice to another person to commit suicide. The Northern Territory legalised euthanasia but the Howard government intervened to override it.

With AAP

On Sunday 19 September 2010 ABC news bulletins broadcast Greens senator Bob Brown stating that he was going to re-introduce euthanasia bills into federal parliament because the Howard government had overturned the rights of the Northern Territory and the ACT territory to have certain bills passed by their parliaments allowed.

The item below comes from the ABC's PM programme and relates to South Australian parliamentarians from 4 sides of politics preparing to introduce a euthanasia bill into their upper and lower houses of parliament.

Here is the interview and the ABC's web site for this PM broadcast:

http://www.abc.net.au/pm/content/2010/s3012861.htmPaula Kruger reported this story on Wednesday, September 15, 2010

MARK COLVIN: Political forces that usually compete have united in South Australia's parliament to try to legalise voluntary euthanasia.

Four MP's including a Labor member, a Green, a Liberal and an independent are publicly supporting the new push which would see two identical bills introduced in both houses of Parliament.

The MP's say there is broad public support for responsible voluntary euthanasia laws, but it is still a very sensitive issue.

The latest attempt to change the law comes just days after a television advertisement supporting voluntary euthanasia was banned on the grounds that it promoted suicide.

Paula Kruger reports.PAULA KRUGER: Despite many attempts to legalise it in different jurisdictions around Australia, euthanasia is still unlawful.

For those who oppose it, it comes down to the basic principle of no one has the right to take the life of another.

But it appears many Australians are comfortable with balancing the right to die with the right to life, with polls showing that more than 80 per cent support voluntary euthanasia.

And that is a figure that brought four South Australian MP's together to give a collective push to the state's effort to legalise euthanasia.

Greens Leader Mark Parnell.MARK PARNELL: We have always known that voluntary euthanasia has overwhelming support in the community but it hasn't had overwhelming support in the Parliament. What we're doing now is we are introducing on a cross-party if you like, or even a multi-party basis, a new bill into both the Lower House and that will be introduced tomorrow, and in the Upper House, which will be introduced in a fortnight. Bills to provide for dying with dignity.

PAULA KRUGER: It's not the first time the Green's leader has tried to introduced voluntary euthanasia legislation in South Australia.

Last year his bill was narrowly defeated in the Upper House. The new legislation is similar but with added safeguards.

Labor MP Steph Key will introduce one of the bills in the Upper House tomorrow.STEPH KEY: When you have a public opinion and also a need for this as an option, I think we're all dedicated to keep campaigning.

PAULA KRUGER Reflecting the unusual unity that comes with a conscience vote was Liberal MP Duncan McFetridge.DUNCAN McFETRIDGE:I just hope that my colleagues who have concerns about this go back to their constituencies and ask them; what do they want them to do? Because as a representative of my electorate in Morphett, I know that over 80 per cent of my electors are behind me in supporting this motion.

PAULA KRUGER: Also standing up to support today's announcement was Geoff Brock, independent member for Frome.GEOFF BROCK: I don't think people realise until they've been through it themselves with their own family, the trauma and the heartache and it's a very, very traumatic experience to see somebody who you know is going to die and they can't do anything about it.

PAULA KRUGER: But despite figures showing strong support for responsible voluntary euthanasia legislation, it is still proving to be a highly sensitive issue.

On Friday afternoon permission to air an ad supporting voluntary euthanasia was withdrawn after the regulatory body responsible for approving ads ruled it promoted suicide.

That has stirred a separate legal fight, this time involving Australia's freedom of speech laws.

Greg Barns is a barrister and Director of the Australian Lawyers Alliance and has also done pro-bono work for Exit International, the organisation that made and paid for the ad.GREG BARNS: This advertisement was not about telling people how to suicide, as the commercial television stations would have us believe; it was an information ad, it was an advocacy ad and it was a political advocacy ad. And it's very important that as the High Court has said on a number of occasions, that political communication be free.

You'd certainly be able to challenge the decision if you had a charter. One of the problems in Australia is that there are no adequate protections for human rights and so people such as Exit International would be able to challenge this decision if there were a Human Rights Act or a Charter of Rights as exists in the UK or in Europe or in Canada.

PAULA KRUGER: Because Exit International can't legally challenge the ruling they may have to alter the ad if they want it to appear on Australian commercial television.

MARK COLVIN: Paula Kruger.

LABOR and the Greens have shown a lack of integrity by moving on voluntary euthanasia straight after the election rather than before it, Melbourne Anglican Bishop Philip Huggins said yesterday.

Bishop Huggins has asked the national parliament of the Australian Anglican Church, now meeting in Melbourne, to affirm the sanctity of life as God's gift. The motion says: ''Our task is to protect, nurture and sustain life to the best of our ability.''

He told The Age he was shocked at the report yesterday that Prime Minister Julia Gillard was backing a conscience vote to restore the power of the territories to allow euthanasia.

The Howard government overturned a Northern Territory decision to allow it in 1997. Bishop Huggins said: ''This was not a matter of pre-election debate. Would people have voted the same way if they knew a Labor government with the Greens would, as a near-first action, promote a conscience vote on euthanasia?

''There would be more integrity in foreshadowing this proposal before an election rather than immediately after. It should have been made plain during the election campaign. There should be a broad-based public debate.''

Greens leader Bob Brown tried to legalise euthanasia in 2007, but both main parties voted against his motion. In 2008 Senator Brown twice introduced a bill to restore territory rights over euthanasia, and the latest move is his third attempt with that bill.

Bishop Huggins said the motion, reaffirming the traditional Christian view, showed the Prime Minister and Parliament that the church would not be silent on this issue.

''We've all been close to people who have had a hard and difficult death,'' he said. ''We have watched and prayed in some anguished places, and can well understand why the idea of euthanasia attracts support.

''However, we also understand what a threshold we cross when our efforts are not focused on protecting life, and providing comfort and pain relief until life ends.''

His motion probably cannot be put to the synod until Thursday, but Bishop Huggins expects a resounding affirmation.

Sydney Archbishop Peter Jensen said he was immensely sympathetic to the motives driving the push for voluntary euthanasia, having watched his mother die. But those pushing for it were out of touch with the reality of human nature.

''It will be a very bad thing for Australian society to break down the key barriers which stand between us and a brutal world,'' Dr Jensen said.

The Victorian Greens said it was ''inevitable'' euthanasia laws would again be debated by State Parliament. Greens MP Colleen Hartland said she would press Attorney-General Rob Hulls to refer the issue to the Law Reform Commission, so the right to die laws could be dealt with by Parliament in the same way as the decriminalisation of abortion.

In 2008, a conscience vote of upper house MPs defeated a euthanasia private member's bill.

With DAVID ROOD

I'M OF German heritage. Both my parents grew up in Nazi Germany and were profoundly affected by World War II.

I have also watched both of them die before my eyes, my mother from cancer just a few weeks ago.

I know exactly what it is like to watch a loved family member and close friend die in pain. Given that my first birthday without her was just Sunday, my grief is still fresh. Many others who oppose euthanasia ''reform'' have similar experiences.

Anyone who thinks that democracy can be utilised to decide on the right to live has obviously not thought about how that power can be abused, nor that it is already abused in places where euthanasia laws have been relaxed. The problem is that the dead don't complain if they didn't want to die.

What is most frightening is that we have a prime minister who has no understanding of this, nor of the logic that democracy itself assumes the right to life as a given, so to vote on this issue is already an act that is logically inconsistent.

That we should even consider blundering towards an abhorrent moral vacuum like this again and attach the debate by inference to a good ''conscience'' borders on the most profound of evils.

Mark Rabich,WHY do those who oppose choice in dying refer to conventions and then usually Nazis, but never the actual suffering and actual wishes of those who would be affected by this 21st century legislation?

Why do they always talk about the hypotheticals, rather than the facts, such as the successful implementation of physician-assisted dying legislation in places such as Oregon and Washington?

Dying with dignity is not an esoteric argument: it's about competent adults deciding on their own medical care. They shouldn't be forced to suffer by the comfortable armchair philosophers. Everyone should have rights over their own bodies, particularly this last right.

Janine Truter, The BasinIN REPLY to Barbara Weeber (Letters, 20/9), this is the very reason that euthanasia should not be legalised. Who decides how lucid an elderly or sick person is before they are given access to life-taking drugs? There have been and would be instances of depressed or senile relatives led to committing suicide with no protection from the law.

There would be pressure on hospitals and nursing homes to ''rationalise'' their budgets and decide who deserves to live and who must die for the common good. There is a radical group lobbying for change in legislation. We must not allow the minority to decide for the majority of Australians.

Helen Leach,BendigoALICE Woolven (Letters, 20/9) cites Article 3 of the UN Charter of Human Rights in her argument against euthanasia: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. In an ideal world, nobody would be deprived of their life against their wishes, but the death sentence continues in many UN member nations, including the United States. Imprisonment denies millions of their liberty, as do laws against euthanasia, which deprive desperate people of their right to end their life at a time of their own choosing.

John Arthur Goodwin,DEAR Coalition, you would be surprised at how many Australians feel that human rights issues, such as euthanasia, are just as important as the economy.

Shauna Tansey, Upper BeaconsfieldRESPONDING to the Greens' proposals on euthanasia, Christopher Pyne says Parliament will be a shambles if distracted from the economy. Can't the Liberals walk and chew gum at the same time?

Hans Paas, CastlemaineADAM Bandt's how-to-vote cards listed 16 policies, without a word on euthanasia. Now, a month later, it is one of the Greens' top priorities. I wish they were honest about their plans when they asked for our votes.

Kevin McGovern, East MelbourneWE ALLOW thousands of people to end their lives each year with the help of the alcohol industry and thousands more, aided by the tobacco industry. So, with the assistance of trained medical professionals, why not allow terminally ill and suffering patients to decide to end their own lives too? It seems only fair. After all, a lot of them are those same people.

Alicia Vaughan, Wangaratta

Article in The Age 22 September 2010:

My first patient for the day is Mrs East. She is 97, a former ballerina who at 92 still caught the train to drop into the casino when she felt in the mood. At 95 she slipped and broke her hip. The hip was replaced but not her confidence.

She protested against being moved into a nursing home but, once there, grew to like it. She couldn't believe that someone would bring her a meal if she just said the word. Her nurse pinned all her dancing medals and ribbons to a wall where she could enjoy them.

Last year, she became a little forgetful. She could recognise her eight children and 20 grandchildren but she was no longer so good at remembering the 10 great-grandchildren. But the family loved her and took pains to make her feel normal. On her 97th birthday, Mrs East spat out her birthday cake, saying it hurt to swallow. Two days later she was diagnosed with advanced oesophageal cancer. She declined any form of treatment, opting for comfort measures alone. Although her memory wasn't great and she needed to keep a log of which family member she had spoken to, she made it clear to all her children that she considered herself to have led a good life and was not afraid to die. In fact, she joked, since her beloved football team was having one of its worst seasons, she was keen to shield herself from further ignominy!

Overnight she takes a turn for the worse. She experiences pain and her breathing becomes rapid. The nurse calls in the family. A son and daughter have been there for hours before I arrive in the morning. Her son reports that she has opened her eyes once to acknowledge them but does not want to talk.

''I think that she is just preparing to die,'' he says.

I nod. ''That can happen.''

Three days later, Mrs East is lying in exactly the same position. The bedside table has been cleared of the various drinks and straws, replaced by a digital frame that keeps projecting photos of her photogenic clan. The motionless patient does not open her eyes to see them. Her daughter follows me out of the room. ''Doctor, it's not long now, is it?''

''No,'' I say, squeezing her hand. ''I don't think so.''

She nods with relief. ''We have prepared for this for months.''

It is this confidence that death is imminent that triggers the automatic caution switch in me, the one that all doctors carry, the one that relatives love to hate. ''I hope for her sake and yours that she goes soon, but,'' I continue reluctantly, ''sometimes even elderly people can hang on for a while.''

The inevitable question - ''What's a while, doctor?''

I cannot believe my eyes but 10 days later, I am still standing at the foot of Mrs East's bed. I stroke her arm and then, in the absence of a response, simply stand and watch the rhythmic rise and fall of her chest. The family has stopped following me in for an update.

Outside the room, I run into her son. A burly man, he is bleary-eyed from having slept in a chair for the past seven nights. He comes straight to the point. ''Doc, this is inhumane. I can tell you that if it was one of my cattle dying like this, I would have shot it, done anything to end its suffering.''

The analogy is a familiar one to many oncologists; although it makes sense on one level, I find it difficult to base my decisions by equating cattle to human.

''Surely, in this modern era, there is something you can do?'' he pleads.

''I assure you that we are doing everything to keep her comfortable and nothing to prolong her life.'' It sounds odd, an apology that says, ''I am sorry your mother won't die.''

It is then, his voice muffled by wads of tissues, that he drives the point home.

''I started off feeling sad for mum. But we had talked about it and I really felt that she was ready to die. She misses dad and all her friends, there is nothing that she longs to do any more, and she just wants to go in peace.

''But here she is, something in her body just not surrendering when her mind is made up. And you know what this does to us as a family? It replaces images of a wonderful and rich life with those of aimless suffering and a drawn-out death.''

I desperately want to help. But this time, for a change, there is no life support to unplug or chemotherapy to stop. It is simply waiting for nature to takes its course.

''Euthanasia is against the law,'' I say gently.

He chokes on his tears. ''I hate myself so much for being angry that mum won't die. I should be sad, but I am not. This is not my mum any more, I want this to end.''

I find myself telling the truth, ''I, too, wish she would die.''

He looks up at me, as if suddenly he has found an ally. ''Doc, I don't know how you guys deal with this stuff. This is painful. I am going home, call me when it's over.''

One by one, the whole clan follows his lead, despondent and shaken. Only one daughter stays behind, reluctantly. I see a family united in grief dispersed in confusion, their pain not only unresolved but seemingly exaggerated. Where there was one patient, we may have created more.

Some days I muse about the slippery slope argument but today would have been a good day to discuss euthanasia.

Mrs East died after another 24 hours, having spent nearly two weeks in an unconscious state.

Ranjana Srivastava is a Melbourne oncologist. She is the author of Tell Me the Truth: Conversations with my Patients about Life and Death.

I HAVE ''DWD'' tattooed on my forearm. It stands for ''dying with dignity''. I am documenting advanced health directives in the event that I become seriously ill or, like my mother, develop Alzheimer's.

She used to work at a nursing home. When she came home she would say: ''Don't ever put me in one of those places. Take me out the back and shoot me first.''

At 70, we had to put her in one of those places and, at 75, she died without dignity, choking as her swallowing muscles ceased to work. For some time, she could not talk, walk, read, watch television, feed herself, or use a toilet. She could, however, emit an inhuman howl for long periods of time and staff would put Mum in the ''quiet room''.

Sydney Archbishop Peter Jensen talks about breaking down ''key barriers which stand between us and a brutal world'' (''Anglicans oppose euthanasia move'', The Age, 21/9). Does he know about wars, slavery, criminal gangs?

Voluntary euthanasia is not brutal, it is gentle and welcomed by many. It's time religious folk like Jensen butted out of what I want to do with my life and my death. It's nothing to do with them.

Helen Smith, Maldon

BARNEY Zwartz's article would be more appropriately titled ''Anglican Church hierarchy opposes voluntary euthanasia''.

This would better reflect the reality of the overwhelming support by the laity in Australia for such a legal right. It would also better reflect the grounding of existing and any future legislation in informed consent.

It is a bit disingenuous of Archbishop Peter Jensen to argue that voluntary euthanasia is a barrier that stands between us and a brutal world.

The archbishop might instead reflect on how a brutal world is sustained by barriers thrown up by opposing human freedoms and failing to support people in making their own difficult decisions in the face of intractable suffering. These barriers surely represent highly conditional compassion.

Julia Anaf, Norwood, SAAFTER reading the commentary in The Age about Bob Brown's support to reinstate territory rights, it is clear the real issue has been forgotten.

The issue is not euthanasia. It is allowing the territories to be able to govern in the way their residents see fit - without outsiders like Kevin Andrews imposing their will because they think they know better.

In the case of the Northern Territory, this could well include the ability to reinstate euthanasia. But this was not the first or last piece of NT legislation to be overturned by the federal government - its regulation of health professions, such as counsellors and naturopaths, is another. The ACT's Civil Unions Act 2006 was overturned in the same way.

Brown's bill should be seen for what it is - an attempt to restore full democratic rights to half a million Australians, and should not be an exercise in moralistic fear-mongering.

Jon Wardle, Paddington, QldEUTHANASIA is always presented to us as a choice for the dying. Given humankind's ability to corrupt anything and everything, how can we prevent euthanasia becoming a choice for the living?

Ian Dennehy, Beaumaris

The following two articles are interesting because of the dates on which they were written and I thought it would be interesting to juxtapose them for purposes of comparison - then and now!

The decision on whether and how to tell patients they have a terminal disease can have a telling effect on doctors.

KENNETH FREED reports from New York on this situationStillness shrouded the room, muffling even the bleep of the heart monitoring machine and the gurgle of the respirator. A human being was about to die.

A 26-year-old woman lay unmoving on the bed. The cancer on her brain already had snuffed out the awareness that separates the living from the dead. A doctor, with the patient’s mother holding firmly to his hand, reached for the resuscitator connection and pulled it.

For 10 almost unendurable minutes, the doctor and mother watched silently as the pulsating line on the monitor slowly evened and then went flat. The beep became a droning tone. A life was “terminated”.

In another hospital at another time, a different doctor sat in an examination room with a woman also dying of cancer. All the sophisticated means at his profession’s command - radiation therapy, surgery, drugs - could do nothing more than still some of the pain, temporarily.

The question came: “Is my illness terminal?”

The doctor was taken aback. He had not mentioned death directly but he had explained the statistics, had held nothing back, had raised no false hopes.

So he answered: “Yes, your condition is terminal.” With those words, he recalled, she “dissolved in front of me.”

Yet a different scene: A young woman with old-fashioned ideas of love and sexual behaviour listened as the doctor explained that the surgery and radiation used to treat her ovarian cancer had all but eliminated any chance for satisfactory physical love in the short time before her death.

“I’ve waited so long to start living and now I’m going to die,” she told the physician.

“Terminal,” “terminated,” mechanic’s words, impersonal expressions used by doctors in the same way outsiders talk about their own jobs.

But is it the same? How does a person whose career is dedicated to saving, healing and prevention deal with agony, disfiguration and death?

Several doctors and nurses who treat cancer patients exclusively were interviewed about the psychological and emotional stresses of their jobs and how they cope with those stresses, if they do.

Nearly everyone knows of doctors who seem to have built a wall, a callus of indifference against the suffering and despair of their patients: distant authority figures who condescendingly treat patients like so many defective machines.

For the most part, though, those interviewed for this story showed deep feelings for their patients and a constant awareness of the psychological needs of those under treatment.

To the doctor, a radiation therapist, who told his patient she was terminal, the episode taught him an indelible lesson.

“I could never do that again,” he said. “She was devastated. I’ve never used that word again….. There is a away to be realistic which is supportive, and there is a way to be realistic which is cold. I’ll never be cold again.”

The doctor who said this is a 41-year-old mid-western who trained as a radiation therapist in some of the best medical schools and institutions in this country and overseas and who has been treating cancer patients for 12 years. He requested anonymity and will be called Dr J.

Do you run into cases, even after all these years, that make you cry? He was asked. “Oh, yes,” he replied. “What I do is get up and wash my hands. I wash my hands a lot.”

Without ever mentioning it, Dr J. leaves an impression that, while he is friendly, he is not really a friend. “I can be a friendly doctor, but I think the patients need to have me in a white coat, and they never call me Jim,” he said.

The patients “need to have me for an authority figure, someone they can put their trust in, and you don’t do that with someone you sit down with and play bridge with and call Jim.”

“I think it is necessary for them to feel that the doctor is thinking about their problem rather than that Jim is thinking about their problem.”

It seems almost universal among doctors to touch patients in a friendly manner, but Dr J. talked about the need for touching with intensity. “I always touch them, always, always. That is very important.”

Another doctor interviewed did not mind being named. He is Michael Van Scoy-Mosher, a 36-year-old New Yorker who affects a hip style, mod clothes, neck chains, open shirts and a hair style best described as a curly bush.

But this apparent playboy has what all the others agree is the toughest practice of all. Van Scoy-Mosher is an oncologist – a tumor specialist. He gives chemotherapy and usually attends cancer victims when they are taken to the hospital to die.

He described his practice with three other oncologists.

“About a third of the practice dies within a given year. Something we don’t deal with is taking care of terminal people. We deal with taking care of patients with cancer, their families, getting the most out of whatever they can.”

This distinction is critical, Van Scoy-Mosher believes. He is not shepherding dying people on their way to the grave, but rather helping them live in the time they have.

“Cancer is another government within your body. It has its own laws and it runs the show,” he said.

“The patients become dependent – the family runs their lives, the doctor runs their lives, everybody runs their lives. We have to try to restore them to the controls.”

Just as Dr J. finally saw the stress build until it forced him away, Van Scoy-Mosher has reached his limit and he, too is pulling back.

He is pulling out of his practice to take a teaching position, although he will continue to treat a small number of patients.

This article was in The Age newspaper:

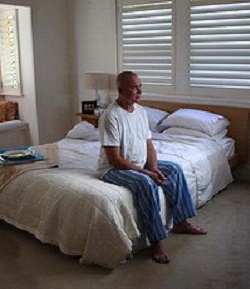

Rudi Dobron wasn't scared of death, but he was scared of dying without dignity. The terminal cancer patient thought palliative care would spare him that ordeal, but his partner says things turned out worse than either of them imagined.

SOON after Rudi Dobron was told his cancer was terminal in 2008, a palliative care nurse asked him if he was scared of dying. It was a confronting question for the 67-year-old, who did not like to talk much about his feelings, but he answered anyway.

''He said, 'I'm not so much fearful of death, but more about the way I die,''' his partner, Bev McIntyre, recalls. ''In response, the nurse said something like, 'Don't worry, you will be given a few shots and out you go.' I remember thinking, oh well, that doesn't sound so bad.''

But what was in store for Dobron over the next seven weeks was worse than he or his partner had imagined.

As a throat and oesophageal cancer patient, he had already endured five surgical procedures, the last of which took his voice away and made it difficult for him to swallow. To communicate, he usually wrote notes on a magnetic board.

As death crept closer for Dobron and he was admitted to Caritas Christi Hospice in Kew, he gave staff an advance directive that documented his desire to die as quickly as possible. The directive said he did not want to be artificially fed, nor did he want to be resuscitated if his heart stopped or if he suffered a catastrophic bleed. He felt his quality of life had already deteriorated beyond repair. All he wanted was to slip quietly away.

McIntyre remembers the directive being noted by a doctor. But within days, Dobron's struggle to swallow meant he was offered artificial feeding through his stomach. He declined. ''Rudi felt that if he took any sustenance, his life would be prolonged, so he said no. He didn't want anything that would do that, particularly if it involved another operation, so the only option was to starve and dehydrate himself to death,'' McIntyre says.

Dobron made it clear to staff that he did not want any food or fluids, but McIntyre says the offers kept coming. ''I don't know whether the doctor had a duty to keep asking every day or not, but it annoyed Rudi. The girl who came around with the menus would come in every day, too. She just kept coming, even though Rudi was saying no.''

As Dobron started to lose control of his bowels and was battling headaches in his second week, he told staff he wanted to be sedated. His medical record states that on his 11th day in the hospice, he just wanted to be unaware.

The intervention was discussed but was not forthcoming. Soon after, Dobron's frustration with his situation peaked and he put pen to paper. In a note handed to McIntyre, he wrote: ''I am dying of cancer of the throat. I can no longer control my bowels, nor eat or drink. If I was a pet, I would have had a peaceful injection days ago. But I am human and so I will have to go through the barbaric religious ritual of dying without dignity from dehydration over weeks. Incidentally, I am an organ donor. By the end of this type of death, my kidneys and other now healthy organs will be dead. Can't eat or drink anything. Been still losing fluid for five days now getting increased dosage of morphine and other stuff.''

Dobron told McIntyre that he had considered sending the note to The Age, but decided not to because he did not want to cause trouble for the hospice.

McIntyre says: ''I thought the note sounded like a note from an explorer who realised he was lost in a desert, not an intelligent, thinking person in the middle of Kew with all amenities on hand.

''Rudi had reached the stage of not being able to swallow his own saliva, so he had to keep spitting. He would rinse out his mouth with soda water to eliminate what must have been intense dryness.''

Around this time, a staff member wrote in Dobron's file that he felt as if he was choking and he had a scared look in his eyes that they had not seen before.

Dobron was slowly deteriorating. Over the next two weeks, he became progressively more dehydrated, with headaches, nausea, shortness of breath and a pressure sore.

He was embarrassed to be wearing a nappy for incontinence and had terrifying hallucinations, including ones of huge insects running on the walls around him.

His doctors say they responded to these symptoms in a way that allowed Dobron to stay alert and interactive, which they believe he wanted at the time. But McIntyre says his physical and psychological suffering was not relieved the way she thought it would be.

''All this time, the medics said he was not in pain and that he was comfortable, but I don't think that was the case. One day I was told he was peaceful, only to walk into his room and find him trying to get out of bed. He was very agitated at times, pulling off his bedclothes and writing about his hallucinations. It was very hard to watch,'' she says.

On Dobron's 27th day in the hospice, his file says he was fed up and anguished. His doctors increased the sedation he was receiving, but it was a week before he was unresponsive and another week before he died. He had been in the hospice for 47 days.

One of the doctors, Peter Sherwen, says Dobron received very good care within the limitations of his desire not to have any life-prolonging interventions, such as a stent in his throat to help him swallow or tube feeding through his stomach.

He said Dobron had enough medication to control his pain and that when he asked about sedation, it was discussed and he either decided against it or agreed to particular levels. ''Rudi was very keen to not have too many drugs on board so he didn't lose control of his situation. He wanted to stay in control of his decision making,'' Sherwen says.

Dobron understood staff were doing everything they could to make him comfortable while being careful not to prolong his life, he says. Staff were also surprised at how long he lived, given his illness and the risk of complications that could have ended his life suddenly.

''I think we did a really good job,'' Sherwen says. ''I think that when you read the notes, they were overwhelmingly around comfort and him feeling quite well.''

The hospice operates according to the values of the Mary Aikenhead Ministries, but Sherwen says religious beliefs did not affect clinical decisions, including those about deep sedation.

Associate Professor Mark Boughey, director of palliative medicine at St Vincent's Hospital, which runs Caritas Christi, said he had reviewed Dobron's case and agreed with Sherwen's response.

Boughey said that although Caritas Christi welcomed advanced directives, doctors always checked to see if people's wishes had changed. Food and water could sometimes increase comfort and offset unpleasant symptoms in the dying process, and this was why Dobron was offered food and fluids despite his directive.

Boughey added that the palliative care nurse's advice that McIntyre remembered was probably given in the context of what would happen if Dobron suffered a catastrophic event that might be painful at the very end of life.

Dobron was cared for by staff at what is considered to be one of the best hospices in Victoria and yet his partner was unhappy with the care he received.

Is his experience common? And could palliative care services be improved?