LUNATICS RUNNING THE ASYLUM - PRESIDENT AND HEALTH MINISTER - 2001

SEPTEMBER 2007

One of the most comprehensive and up-to-date analyses of the AIDS crisis in South Africa is to be found on this web site: HIV and AIDS in South Africa

The history of AIDS in South Africa is littered with bodies - the bodies of people who in effect have been murdered by the direct actions of a president and his government. The time for mincing words has long passed as those still living in South Africa are able to testify.

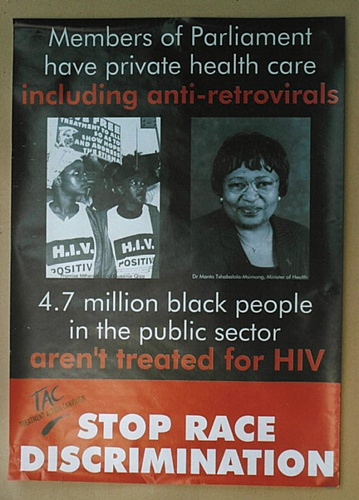

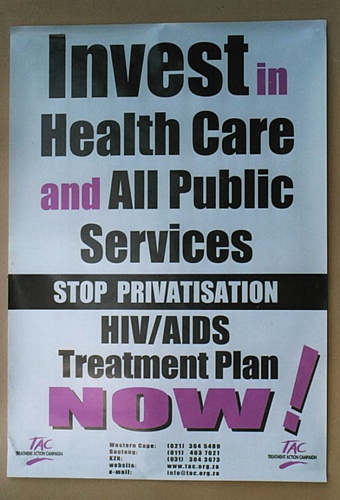

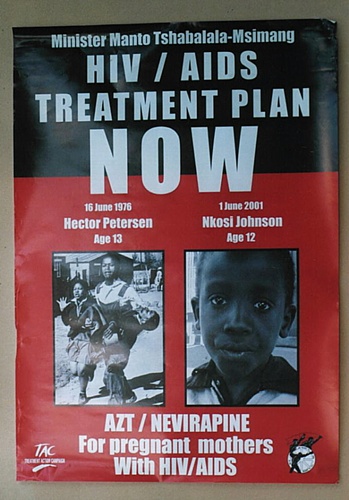

Campaigns by activist groups such as the TAC have achieved some success but the criminals in charge of the hospital are still there and are continuing to wreak havoc on the health of 40 million people, 20% of whom are HIV positive.

What a scandal for a country which is one of the richest on the African continent, with unlimited resources and with the people able to contribute to making it one of the liveliest and most interesting countries in the world.

AUGUST AND SEPTEMBER 2007

The following headlines appeared in South African papers in August 2007 - unfortunately the names and dates of some of the papers were omitted from the clippings sent to us, so we assume they may be mainly from the Sunday Times:

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4) [From the Sunday Times, 12 August 2007]

(5) [From the Sunday Times, 19 August 2007]

11 SEPTEMBER 2007

The following item was in the online edition of the Sunday Times:

I understand that you want us to nominate fellow bloggers but instead Essop Pahad gets my vote. How dare he pull advertising from the Sunday Times just because they published articles about the esteemed Liquor Cabinet Minister Manto Dipstick-Meshugena. — City Slicker

AIDS history starts, in effect, in 1981, when a disease normally afflicting elderly men, Kaposi's Sarcoma, a type of cancer, started being detected in healthy young homosexual men in the USA. It wasn't long before the disease was discovered world-wide and spreading rapidly - among homosexual and heterosexual men and women. Initially little was known about the disease and no treatments were available. Death occurred mostly fairly rapidly, within weeks or months of contracting a disease which had not really been given a proper name. It was not known where the disease came from, whether it was spread from one person to another, and if so, how.

Thabo Mbeki became president of South Africa after Nelson Mandela retired in 1999. Mbeki was thought at the time he became president to be a worthy successor to Mandela because he had been part of the liberation struggle against the apartheid regime while he was in exile. His father, Govan Mbeki had been a close associate of Mandela’s and great hope was placed in his son who was considered a serious-minded intellectual who would lead the country into greater security and prosperity, which Mandela had started to secure from the international community.

Now, at the end of 2007, Mbeki’s government – and the ANC – is plagued by corruption, nepotism, incompetence, and certainly criminal activities, relating to the HIV/AIDS crisis and the continued employment of Manto Tshabalala-Msimang as the Health Minister. The disgraceful scaking of her deputy was an international cause celebre, and did nothing to allay the suspicion that the sacking was engineered by Manto.

Mbeki now wants to exercise greater censorship and hopes to get hold of the Sunday Times newspaper which has continued to expose the corruptions in the government and the ANC. The Sunday Times expose of the Health Minister’s criminal behaviour and her alcoholism should have been enough for Mbeki to investigate her ability and her justification for maintaining her portfolio. Instead he has defended her and wants to bring criminal charges against the newspaper which has exposed the scandals.

The following articles were in The Age newspaper on 10 November 2007, from the Guardian newspaper of the UK, and are of such importance that they are here reproduced in full.

Just as there was international pressure against the apartheid regime, and now the Mugabe regime, so there needs to be international pressure to get Mbeki to resign before he takes over the mantle as the Mugabe of South Africa.

Time too for South Africa’s political groupings to reassess their affiliations and provide a strong parliamentary opposition to Mbeki and the ANC government. It is too easy for Mbeki and his supporters to use the smear of racism in their counter-attacks against their opponents, but they clearly need to be made accountable for their corrupt practices. Manto must be made to go sooner rather than later to remove some of the taints which besmirch the government.

IT'S THE kind of thing that might give a banana republic a bad name: the editor of one of South Africa's biggest newspapers threatened with arrest for exposing a minister as a drunk and a thief while the country's top prosecutor is suspended for investigating corruption allegations against the chief of police.

Thirteen years after President Nelson Mandela inspired the world by overseeing a peaceful transition from apartheid to democracy, the shine has rubbed off his successor Thabo Mbeki. The soft-spoken but aloof academic the West regarded as a safe pair of hands has, according to his critics, become increasingly autocratic and paranoid. He has sacked officials and ministers who fail to show "slavish deference" and is accused of leading an assault on press freedom the like of which South Africa has not seen since the dark days of apartheid. For their part, the President's supporters insist the allegations are baseless and part of a political campaign to influence December's crucial African National Congress conference where Mr Mbeki will bid for a third term as party leader against rivals Jacob Zuma, the former deputy president, and businessman Tokyo Sexwale.

The latest target in what one British newspaper called Mr Mbeki's "paranoid war" is the Sunday Times, the country's biggest broadsheet paper whose exposes have regularly embarrassed the Government.

Alarm bells rang last week when the newspaper reported that its owner, Johnnic Communications, had received a bid by a consortium made up of prominent allies of the President, including his political adviser Titus Mafolo, Foreign Ministry spokesman Ronnie Mamoepa and the former chief of state protocol, Billy Modise.

Despite the insistence by the President's spokesman, Mukoni Ratshitanga, that the President knew nothing about it, the opposition was quick to claim that this was a back-door attempt by the state to gain control of one of its most persistent critics. What on its own might seem a relatively innocuous business deal similar to others involving members of the powerful ANC elite, has taken on a sinister edge because of its timing.

Just weeks earlier, the paper's young black editor, Mondli Makhanya, was allegedly threatened with arrest after publishing a series of embarrassing stories about the country's controversial Minister of Health, Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, based in part on a leaked copy of her medical records.

The newspaper claimed the minister had disgraced herself during a hospital stay in 2005, throwing tantrums and refusing to eat the food. But it was the allegation that alcohol was smuggled into her room and that she was drunk in the hospital on several occasions that struck a chord, appearing to confirm a long-rumoured drinking problem.

A week later the paper alleged there had been a cover-up over a liver transplant that Dr Tshabalala-Msimang had undergone in March after her own liver was said to have been damaged by "auto-immune hepatitis".

In fact, the paper claimed, the minister was suffering from alcoholic liver cirrhosis and she had continued drinking even after the transplant. It also revealed that she had been convicted of theft after stealing watches, jewellery and even shoes from patients at a hospital in Botswana where she had worked as a medical superintendent in the mid-1970s.

The Health Ministry went to court to demand that the medical records be returned. The Cape Town Medi-Clinic, where the minister stayed in 2005, laid a charge of theft against the paper after discovering her medical records were missing.

Last month the newspaper splashed with the news that police investigating the theft had told its editor and his deputy managing editor, Jocelyn Maker, that they would be arrested on suspicion of receiving stolen property. They are also facing charges under the National Health Act, which makes it an offence to publish someone's medical records without their permission.

In the wake of a call by Essop Pahad, Minister in the Presidency, for government advertising to be withdrawn from the paper, many in the media saw it as an attempt to teach the paper a lesson. It was claimed that Mr Mbeki himself was behind the arrests and that a police officer had spent a week in New Zealand to interview the person suspected of leaking the minister's medical records. It was suggested that Ms Maker's phone had been tapped and police had been told to "dig up dirt" on Mr Makhanya and other journalists involved in stories about the Health Minister.

Writing in a British newspaper recently, writer R. W. Johnson compared Mr Mbeki's behaviour to that of Robert Mugabe, President of neighbouring Zimbabwe. Mr Ratshitanga, the presidential spokesman, responded in kind, labelling Johnson a "full blooded racist". There is a strong suspicion that the matter is being pursued with a vigour that is in stark contrast to the resources put into solving many of the 19,000 murders committed last year. Mr Makhanya says he can't discuss the arrest but he is convinced press freedom is under threat.

Also worrying government critics is the ruling ANC's proposal for a media "tribunal" to explore, in the words of ANC information head Smuts Ngonyama "certain biases" within the industry. Karima Brown, veteran political editor of Business Day newspaper (50 per cent owned by Johnnic), points to the recent attempt by the ANC to push a list of approved candidates for the board of the country's largest broadcaster, South African Broadcasting Corporation, as a "clear indication that the state is keen to get its hand on large media institutions".

While the focus has been on the media, there has been a deafening silence from the minister and President on much of the substance of the allegations in the Sunday Times.

On the potentially serious question of whether the minister in charge of the nation's health is an alcoholic, the Government has said nothing.

THE bitter power struggle between President Thabo Mbeki and his former deputy, Jacob Zuma, for control of the ruling African National Congress intensified as a South African court opened the way for Mr Zuma to be charged over a multibillion-dollar weapons deal.

The court of appeal's ruling on Thursday that the police seizure of allegedly incriminating documents from Mr Zuma's home and office was legal was expected to undermine his campaign as the favoured candidate to unseat Mr Mbeki as party leader at an ANC congress next month and so become the country's president in 2009.

The court also said investigators could have access to papers about a meeting between Mr Zuma and a French arms company, Thint, at which the payment of a substantial bribe was allegedly discussed.

After Thursday's rulings Mr Zuma said he would seek leave to appeal to the supreme court. The ruling comes six weeks before the ANC leadership election in which Mr Zuma appears to be the only candidate capable of defeating Mr Mbeki.

Mr Mbeki is constitutionally barred from running again for president of the country in 18 months' time, but there is no legal obstacle to him remaining as the ANC's leader. If he were to win next month's vote, he would probably be able to anoint his successor as president and would have considerable influence in parliament, because the party's MPs would answer to him.

But Mr Mbeki faces strong opposition from the trade union confederation and the Communist Party, members of the ruling tripartite alliance with the ANC, because they are unhappy with the Government's market-oriented economic policies. They have thrown their weight behind Mr Zuma, despite corruption allegations that have dogged him for years.

GUARDIANSOUTH African President Thabo Mbeki's top political adviser and a senior government official have made a bid to buy a leading South African newspaper group embroiled in a battle with the presidency over its exposure of high-level abuse of power and corruption. The attempt to buy Johncom for 7 billion rand ($A1.16 billion) has raised concerns that it is an attempt to silence one of the country's best-selling newspapers, the Sunday Times.

The paper recently alleged that Health Minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang is a convicted thief and an alcoholic who misused her office to obtain a liver transplant while still drinking. The paper has been critical of Mr Mbeki's hostility to the conventional treatment of AIDS, hostility doctors say has cost hundreds of thousands of lives.

It has also accused Mr Mbeki of abusing his powers and using underhand tactics to silence and punish opponents as he struggles to retain the leadership of the ruling African National Congress.

The consortium seeking to buy Johncom includes Mr Mbeki's political adviser, Titus Mafolo, who made headlines five years ago when he was accused of faking his own car-hijacking. He was charged with fraud, perjury and defeating the ends of justice. The charges were later dropped.

Other members of the consortium include Foreign Ministry spokesman Ronnie Mamoepa and a former chief of state protocol, Billy Modise. All are close to Mr Mbeki.

Johncom also owns the Sowetan and has a big stake in the country's leading financial daily, Business Day.One prominent ANC MP, Kader Asmal, said there was a danger of independent newspapers falling under political control. He told the Sunday Times that it is "astonishing that civil servants are able to develop time and energy for what is really a takeover bid".

Mr Mamoepa said the bid was a purely commercial venture, while Mr Mbeki's office said the President did not know about it.

Suspicions that it is politically motivated have been strengthened by the increasingly hostile confrontation between the Sunday Times and Mr Mbeki's office.

Last month, police began a criminal investigation of the paper's editor, Mondli Makhanya, for allegedly obtaining the Health Minister's medical records illegally.

Critics said the assigning of a top detective and considerable resources to the case reflected the political nature of the investigation in a country where there were barely enough resources to deal with the horrific murder rate.

GUARDIAN

Article in Scottish newspaper Sunday Herald

The lights are literally and figuratively going out all over South Africa as crime, corruption and mismanagement push the rainbow country towards becoming another failed African state.

AFTER bathing in the warm, fuzzy glow of the Mandela years, South Africans today are deeply demoralised people. The lights are going out in homes, mines, factories and shopping malls as the national power authority, Eskom - suffering from mismanagement, lack of foresight, a failure to maintain power stations and a flight of skilled engineers to other countries - implements rolling power cuts that plunge towns and cities into daily chaos.

Major industrial projects are on hold. The only healthy enterprise now worth being involved in is the sale of small diesel generators to powerless households but even this business has run out of supplies and spare parts from China.

The currency, the rand, has entered freefall. Crime, much of it gratuitously violent, is rampant, and the national police chief faces trial for corruption and defeating the ends of justice as a result of his alleged deals with a local mafia kingpin and dealer in hard drugs.

Newly elected African National Congress (ANC) leader Jacob Zuma, the state president-in-waiting, narrowly escaped being jailed for raping an HIV-positive woman last year, and faces trial later this year for soliciting and accepting bribes in connection with South Africa's shady multi-billion-pound arms deal with British, German and French weapons manufacturers.

One local newspaper columnist suggests that Zuma has done for South Africa's international image what Borat has done for Kazakhstan. ANC leaders in 2008 still speak in the spiritually dead jargon they learned in exile in pre-1989 Moscow, East Berlin and Sofia while promiscuously embracing capitalist icons - Mercedes 4x4s, Hugo Boss suits, Bruno Magli shoes and Louis Vuitton bags which they swing, packed with money passed to them under countless tables - as they wing their way to their houses in the south of France.

It all adds up to a hydra-headed crisis of huge proportions - a perfect storm as the Rainbow Nation slides off the end of the rainbow and descends in the direction of the massed ranks of failed African states. Eskom has warned foreign investors with millions to sink into big industrial and mining projects: we don't want you here until at least 2013, when new power stations will be built.

In the first month of this year, the rand fell 12% against the world's major currencies and foreign investors sold off more than £600 million worth of South African stocks, the biggest sell-off for more than seven years.

"There will be further outflows this month, because there won't be any news that will convince investors the local growth picture is going to change for the better," said Rudi van der Merwe, a fund manager at South Africa's Standard Bank.

Commenting on the massive power cuts, Trevor Gaunt, professor of electrical engineering at the University of Cape Town, who warned the government eight years ago of the impending crisis, said: "The damage is huge, and now South Africa looks just like the rest of Africa. Maybe it will take 20 years to recover."

The power cuts have hit the country's platinum, gold, manganese and high-quality export coal mines particularly hard, with no production on some days and only 40% to 60% on others.

"The shutdown of the mining industry is an extraordinary, unprecedented event," said Anton Eberhard, a leading energy expert and professor of business studies at the University of Cape Town.

"That's a powerful message, massively damaging to South Africa's reputation for new investment. Our country was built on the mines."

To examine how the country, widely hailed as Africa's last best chance, arrived at this parlous state, the particular troubles engulfing the Scorpions (the popular name of the National Prosecuting Authority) offers a useful starting point.

The elite unit, modelled on America's FBI and operating in close co-operation with Britain's Serious Fraud Office (SFO), is one of the big successes of post-apartheid South Africa. An independent institution, separate from the slipshod South African Police Service, the Scorpions enjoy massive public support.

The unit's edict is to focus on people "who commit and profit from organised crime", and it has been hugely successful in carrying out its mandate. It has pursued and pinned down thousands of high-profile and complex networks of national and international corporate and public fraudsters.

Drug kingpins, smugglers and racketeers have felt the Scorpions' sting. A major gang that smuggle platinum, South Africa's biggest foreign exchange earner, to a corrupt English smelting plant has been bust as the result of a huge joint operation between the SFO and the Scorpions. But the Scorpions, whose top men were trained by Scotland Yard, have been too successful for their own good.

The ANC government never anticipated the crack crimebusters would take their constitutional independence seriously and investigate the top ranks of the former liberation movement itself.

The Scorpions have probed into, and successfully prosecuted, ANC MPs who falsified their parliamentary expenses. They secured a jail sentence for the ANC's chief whip, who took bribes from the German weapons manufacturer that sold frigates and submarines to the South African Defence Force. They sent to jail for 15 years a businessman who paid hundreds of bribes to then state vice-president Jacob Zuma in connection with the arms deal. Zuma was found by the judge to have a corrupt relationship with the businessman, and now the Scorpions have charged Zuma himself with fraud, corruption, tax evasion, racketeering and defeating the ends of justice. His trial will begin in August.

The Scorpions last month charged Jackie Selebi, the national police chief, a close friend of state president Thabo Mbeki, with corruption and defeating the ends of justice. Commissioner Selebi, who infamously called a white police sergeant a "f***ing chimpanzee" when she failed to recognise him during an unannounced visit to her Pretoria station, has stepped down pending his trial.

But now both wings of the venomously divided ANC - ANC-Mbeki and ANC-Zuma - want the Scorpions crushed, ideally by June this year. The message this will send to the outside world is that South Africa's rulers want only certain categories of crime investigated, while leaving government ministers and other politicians free to stuff their already heavily lined pockets.

No good reason for emasculating the Scorpions has been put forward. "That's because there isn't one," said Peter Bruce, editor of the influential Business Day, South Africa's equivalent of, and part-owned by, The Financial Times, in his weekly column.

"The Scorpions are being killed off because they investigate too much corruption that involves ANC leaders. It is as simple and ugly as that," he added.

The demise of the Scorpions can only exacerbate South Africa's out-of-control crime situation, ranked for its scale and violence only behind Colombia. Everyone has friends and acquaintances who have had guns held to their heads by gangsters, who also blow up ATM machines and hijack security trucks, sawing off their roofs to get at the cash.

In the past few days my next-door neighbour, John Matshikiza, a distinguished actor who trained at the Royal Shakespeare Company and is the son of the composer of the South African musical King Kong, had been violently attacked, and friends visiting from Zimbabwe had their car stolen outside my front window in broad daylight.

My friends flew home to Zimbabwe without their car and the tinned food supplies they had bought to help withstand their country's dire political and food crisis and 27,000% inflation. Matshikiza, a former member of the Glasgow Citizens Theatre company, was held up by three gunmen as he drove his car into his garage late at night. He gave them his car keys, wallet, cellphone and luxury watch and begged them not to harm his partner, who was inside the house.

As one gunman drove the car away, the other two beat Matshikiza unconscious with broken bottles, and now his head is so comprehensively stitched that it looks like a map of the London Underground.

These assaults were personal, but mild compared with much commonplace crime.

Last week, for example, 18-year-old Razelle Botha, who passed all her A-levels with marks of more than 90% and was about to train as a doctor, returned home with her father, Professor Willem Botha, founder of the geophysics department at the University of Pretoria, from buying pizzas for the family. Inside the house, armed gunmen confronted them. They shot Professor Botha in the leg and pumped bullets into Razelle.

One severed her spine. Now she is fighting for her life and will never walk again, and may never become a doctor. The gunmen stole a laptop computer and a camera.

Feeding the perfect storm are the two centres of ANC power in the country at the moment. On the one hand, there is the ANC in parliament, led by President Mbeki, who last Friday gave a state-of-the-nation address and apologised to the country for the power crisis.

Mbeki made only the briefest of mentions of the national Aids crisis, with more than six million people HIV-positive. He did not address the Scorpions crisis. The collapsing public hospital system, under his eccentric health minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, an alcoholic who recently jumped the public queue for a liver transplant, received no attention. And the name Jacob Zuma did not pass his lips.

Last December Mbeki and Zuma stood against each other for the leadership of the ANC at the party's five-yearly electoral congress. Mbeki, who cannot stand again as state president beyond next year's parliamentary and presidential elections, hoped to remain the power behind the throne of a new state president of his choosing.

Zuma, a Zulu populist with some 20 children by various wives and mistresses, hoped to prove that last year's rape case, and the trial he faces this year for corruption and other charges, were part of a plot by Mbeki to use state institutions to discredit him. Mbeki assumed that the notion of Zuma assuming next year the mantle worn by Nelson Mandela as South Africa's first black state president would be so appalling to delegates, a deeply sad and precipitous decline, that his own re-election as ANC leader was a shoo-in.

But Mbeki completely miscalculated his own unpopularity - his perceived arrogance, failure to solve health and crime problems, his failure to deliver to the poor - and he lost. Now Zuma insists that he is the leader of the country and ANC MPs in parliament must take its orders from him, while Mbeki soldiers on until next year as state president, ordering MPs to toe his line.

Greatly understated, it is a mess. Its scale will be dramatically illustrated if South Africa's hosting of the 2010 World Cup is withdrawn by Fifa, the world football body.

Already South African premier league football evening games are being played after midnight because power for floodlights cannot be guaranteed before that time. Justice Malala, one of the country's top newspaper columnists, has called on Fifa to end the agony quickly.

"I don't want South Africa to host the football World Cup because there is no culture of responsibility in this country," he wrote in Johannesburg's bestselling Sunday Times.

"The most outrageous behaviour and incompetence is glossed over. No-one is fired. I have had enough of this nonsense, of keeping quiet and ignoring the fact that the train is about to run us over.

"It is increasingly clear that our leaders are incapable of making a success of it. Scrap the thing and give it to Australia, Germany or whoever will spare us the ignominy of watching things fall apart here - football tourists being held up and shot, the lights going out, while our politicians tell us everything is all right."

BMJ Group blogs (British Medical Journal)

South Africa’s newly elected president, Mr Kgalemo Mothlante, acted swiftly to end an era of ugly controversy and extreme incompetence in the health ministry by appointing a highly regarded, new health minister and effectively demoting the previous one, Dr Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, who implemented all of former president Thabo Mbeki’s eccentric AIDS beliefs, which has laid the foundations for the increased burden of disease that South Africa now has.

Within hours of his inauguration he appointed to cabinet, Ms Barbara Hogan, one of very few white women sentenced to a long stretch (10 years) in prison for treason by the apartheid government. Since then, she has chaired parliamentary committees on finance and on the auditor general, as a member of the ruling party, the African National Congress, has been noted not only for efficiency and intellectual astuteness, but for not being afraid to challenge the former president’s views on AIDS and make her own views known by siding with the activist groups trying to change AIDS policies.

As one of very few high-profile changes to government, her appointment signalled the urgency with which the new government needed to rid itself of what has been repeatedly referred to as destructive and divisive era of health policy and care. It has not been limited to a few disgruntled voices to criticise the previous president and his health minister - political commentators, journalists, broadcasters, trade unionists, and others have all clamoured in this recent fortnight of turmoil to be heard noting Mr Mbeki’s AIDS legacy.

It would not have gone without notice either, that on the day of the inauguration, and effective demotion of the previous health minister, yet another TV news item showed a community’s discontent with its large, but ill-equipped hospital. The Carltonville hospital, serving a large and impoverished population outside Johannesburg and close to many gold mines, had seen the deaths of three patients who had fallen out of a broken window with, it was alleged, insufficient reason for this. Protesters and patients outside the hospital complained that a doctor was available only once a month and that nurses beat patients. It is another unfortunate legacy of the Mbeki-era that patients’ complaints of failing services have fallen on deaf ears and resulted in frequent similar stories in the media. In the TB arena, viewers used to thinking of the occupants in hospitals as “patients” have become used to stories in the media, of patients who have “escaped” their quarantine facility and are being hunted down by police, like criminals.

While nobody has diminished the enormity of the task of repairing the damage to the health of all but the small white minority population, caused by apartheid, the small hints at improvements to the country’s vital statistics during the tenure of president Nelson Mandela (among them a small drop in the infant mortality rate) were rapidly undone when Mr Mbeki assumed office in 1999, announcing shortly afterwards his intention to follow up his inquiries into already well accepted AIDS science. His health minister, Dr Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, although struck off the professional register in Botswana for her theft of patients’ belongings while in exile, became his loyal hatchet-man when after several years of blunt refusals to listen to wiser counsel, Mr Mbeki was eventually forced to keep quiet on health issues.

Ironically, had he but listened to Mr Mandela in one of several meetings within the ANC on the AIDS issue and anti-retroviral therapy, and heeded a very pointed warning, Mr Mbeki may well have avoided his sacking. On that day, Mr Mandela told the meeting that it was not unprecedented within the ANC for it to depose a leader who had lost favour. He cited the one little known instance when this had happened as a way of warning the president that his party was capable of running out of patience and loyalty and sacking him too . However, it was not only the president who failed to heed the warning, but the majority of his cabinet and the national executive committee of the party. Almost nobody spoke or voted against the president at that time - but this trickle began to develop into what became a torrent of irritation when activists with doctors, trade unionists and others began using the courts and the constitution to force the government to begin providing ARV treatment. More importantly for a president who was fired in part for letting go of the ANC’s policy of alleviating poverty and creating jobs, the government found itself baring the brunt of démarches from Western embassies, deputations from multinational pharmaceutical companies, threats from prospective donors to his pet projects within Africa to withdraw their backing, and finally his own ambassadors and a large and influential grouping of black businessmen. While he became quiet, his health minister took over startling and dismaying local and foreign experts with her preference for beetroot and traditional medicines to treat AIDS.

Mr Mbeki’s legacy, from one of AIDS denialism, also incorporates after the long battle, the fact that the country now has the largest anti-retroviral programme in the world. It took subterfuge within the Treasury and certain people in the health departments to ensure that enough would be found to budget for the programme so that resources could not be used as an excuse to continue to deny ARVs to people in need of them.

However, the health system has been bleeding professionals with doctors and nurses trained in South Africa, leaving the country in droves and doctors from Tunisia and Cuba among other countries, being recruited to work in South Africa. This has left less skilled and sometimes incompetent people in the country. The same pattern has been mirrored in the health department itself with those able to get jobs leaving and those remaining not able to make headway in improving health.

At a recent conference in Cape Town of several United Nations groups on mother and child survival, it was noted that in the area of child deaths, South Africa was one of the 10 worst performing countries in the world and would not meet its Millennium Goals for the Countdown to 1015 for Maternal, Newborn and Child Survival in health.

The conference heard that at least 260 women babies and children died daily in South Africa and no progress had been made to reduce this. Making matters worse, many of these deaths were caused by inadequate care by health care workers. The figures were worse than those during apartheid.

There are few if any experts who would now jump to the defence of former president Mbeki’s health legacy, partly because so many people are part of communities robbed of young lives from AIDS and because it is likely to become as unfashionable to defend his policies as it suddenly became to defend apartheid in 1994.

Pat Sidley is a medical journalist in Johannesburg.5 Responses to “Pat Sidley on South Africa after Mbeki”

1. Pat Sidley fundamentally misstates how South AFrica’s black government makes its decisions on issues like AIDS. As President Motlanthe said yesterday, these decisions are made by the collective,not by any individual. Sidley confuses the authorities of the President of the United States or some other strong presidential system with the South African system in which the president is basically a prime minister with a presidential title and who is accountable to the cabinet and the party caucus in the National Assembly. To personalize policy decision on Mbeki is to be fundamentally misinformed about how South AFrica’s government is run.

The new minister of health will be part of the same collective decision making system as Tshabalala-Msimang and will have to get a consensus in cabinet for any new policy. It is not even clear that the new minister wants any change in policy. But, being from the white English-speaking community, perhaps the white English speakers who viciously attacked her two black predecessors will lay off. At least for a while.

Paul2. Pat is spot on in her article. Mbeki imposed his views on government leadership, which he had filled with yes-men. Ministers, such as the former deputy Minister for Health, who disagreed with him didn’t last long in their post. (But no one ever got fired for incompetence.)

Paul needs to get over his race hangups. Mbeki had the same problem hence he mistook AIDS as a race issue and refused to deal with it, with genocidal consequences for South Africa.

Ravi3. Paul states that decisions are made by the “collective”; in the case of the Ministry of Health, this grouping consisted of a small cabal with a bizarre agenda that attempted to politicise science. The steadfast opposition (and forced change that occurred as a result) by a growing number of incensed ordinary South African health workers and activists was one of the major factors that prevents Mbeki and Msimang being remembered as the Pol Pots of the medical world. I very much doubt if they have the insight to be grateful to them.

Andrew4. Finally after years of Dr Manto Tshabalala-Msimang’s poor handling of what is an AIDS crisis in South Africa, we can finally look forward to some sensible national policy which will deliver appropriate care at the grassroot level.

Vishen5. Mr Mbeki’s legacy, from one of AIDS denialism, also incorporates after the long battle, the fact that the country now has the largest anti-retroviral programme in the world. It took subterfuge within the Treasury and certain people in the health departments to ensure that enough would be found to budget for the programme so that resources could not be used as an excuse to continue to deny ARVs to people in need of them.

——— Mobin

South Africa's new Health Minister has broken dramatically from a decade of discredited government policies on AIDS, declaring that the disease is unquestionably caused by HIV and must be treated with conventional medicine.

Barbara Hogan's pronouncement marked the official end to 10 years of denial about the link between HIV and AIDS by former president Thabo Mbeki and his health minister, Manto Tshabalala-Msimang.

New efforts to find AIDS vaccine

South Africa's new health minister Barbara Hogan signals a fresh approach in the battle to fight AIDS.

Activists had accused Ms Tshabalala-Msimang of spreading confusion about AIDS through her public mistrust of anti-retroviral medicines and promotion of nutritional remedies such as garlic, beetroot, lemon, olive oil and the African potato.

"We know that HIV causes AIDS," Ms Hogan told an international AIDS vaccine conference during her highest-profile public appearance since she became Health Minister two weeks ago after Mr Mbeki was dumped by his party.

"It's even more imperative now that we make HIV prevention work. We desperately need an effective HIV vaccine."

She was praised at the opening ceremony of an international AIDS vaccine conference by international scientists and public health officials who were frequently spurned by the former health minister.

Ms Tshabalala-Msimang's views earned her the nicknames Dr Garlic and Dr Beetroot and made her a favourite target for cartoonists.

South Africa now has the world's highest number of people with HIV, about 5.4 million. Ms Hogan was frank about the cost of the epidemic, which kills nearly 1000 South Africans a day and infects about the same number.

She said more than a quarter of the national health budget went on fighting the disease. She said although South Africa now had the world's largest anti-retroviral program, with 550,000 people on treatment, more needed to be done. It needed to be more community-based, with treatment administered by nurses - a long-standing demand of AIDS activists that the former health minister resisted.

AP

For years, South Africa was an international laughing stock for its tragically absurd approach to the deadly AIDS epidemic. Now, that national nightmare may be ending.

The new government of President Jacob Zuma seems to have a clearer-eyed view of the problem, its remedies and the need to improve the overall health care system than its predecessor did. Fixing what’s broken will not be easy, but we are encouraged by signs of a commitment to do so.

To see how far South African leaders have come, one needs to recall where the country was. The former president, Thabo Mbeki, compiled a record that is still hard to fathom: he embraced crackpot theories that disputed the demonstrable fact that AIDS was transmitted by a treatable virus. He insisted that antiretroviral drugs were toxic and encouraged useless herbal folk remedies instead. He even claimed he knew nobody with the disease, although nearly 20 percent of the adult population is said to be living with H.I.V.

Thousands of Africans were needlessly sickened and died. And the most influential country in sub-Saharan Africa squandered the opportunity to contain the AIDS epidemic. Although it has less than 1 percent of the world’s population, South Africa now accounts for 17 percent of the world’s burden of H.I.V. infection.

A saner approach began to take shape last year after Mr. Mbeki was forced out of office and Barbara Hogan was named health minister. Last week, the new health minister, Dr. Aaron Motsoaledi, went further.

He accepted a withering critique by South African scientists, who said the governing African National Congress party’s record on AIDS and health care was deeply flawed, and promised remedial action. “We do take responsibility for what has happened and responsibility for how we move forward,” Dr. Motsoaledi said in an article by The Times’s Celia Dugger.

South Africa’s leaders must espouse sensible, scientifically based advice about AIDS and put in place programs that seek to both treat and prevent the disease. That means expanding efforts to prevent mothers from infecting their babies, discouraging people from having multiple sex partners and offering circumcision to men, a relatively simple surgical procedure proved to have greatly reduced the risk of infection in South Africa.

The problem is bigger than AIDS. Even though South Africa spends more on health than any other African country, tuberculosis is rampant and child mortality rates are rising. The government must work to improve the quality of health care, ensure that all South Africans have access to the system and fire incompetent staff.

None of this will reverse the damage and deaths of Mr. Mbeki’s disastrous legacy, but it can offer the people of South Africa a better future.

Editorial of the New York Times

This flyer was received from APHEDA-Union Aid Abroad - about AIDS in Zimbabwe and South Africa:

Mannie and Kendall Present: LESBIAN AND GAY SOLIDARITY ACTIVISMS

Mannie's blogs may be accessed by clicking on to the following links:

MannieBlog (from 1 August 2003 to 31 December 2005)

Activist Kicks Backs - Blognow archive re-housed - 2005-2009

RED JOS BLOGSPOT (from January 2009 onwards)

This page updated 21 FEBRUARY 2015 and again on 27 OCTOBER 2016

PAGE 52