For most of my working life - a period of about 40 years - I have belonged to trade unions. My working life has been divided between South Africa and Australia, and it was in Australia that I became an active participant in whichever union I was involved with at the time.

I have always believed that it is necessary for people in the workforce to be able to be protected in matters such as working conditions, wages, and in later years when it became "fashionable", occupational health and safety. In order to present problems to management and to negotiate for the resolution of any problems arising from these matters it is necessary that the workers be effectively represented. It was thus a logical decision, when confronted with a free choice of subject matter to pursue for my investigative report, that I would decide to report on AIDS and the trade unions.

As indicated above, I have had a long-standing involvement with trade unions. Throughout that time, the approaches of unions to protecting the rights and well-being of union members has been a significant personal interest. Thus, the purpose or principal aim of this investigation - to chart the policy approaches adopted by the Australian trade union movement to AIDS in the workplace since the onset of the epidemic in the early 1980s until the present time - arises, logically, from that interest. It is anticipated that in order to achieve this purpose it would be necessary for me to undertake a detailed examination of the AIDS-related content of union journals, newspapers and other relevent documents in order to establish what policy trends have emerged during the past fifteen or so years. Within the context of this examination, it is also my intention to:

It is hoped that this investigation will not only chart progress to date in the development and implementation of AIDS-related workplace policies and strategies but will also indicate the sensitivity of unions in relation to the provisions of the anti-discrimination legislation administered in New South Wales by the New South Wales Anti-Discrimination Board.

Because the potential scope of such a study could be very wide indeed, it was decided, after much discussion, that a case study of a single trade union would, in itself, generate sufficient data to fulfil the requirements of such an investigation. The problem then became one of which trade union to select, there being so many, although with the many amalgamations which have taken place in recent years, the number has shrunk significantly.

I determined that my approach would use a case study approach and focus on one trade union based in Sydney in the hope that there would be sufficient material in a single union's documentation to establish not only its AIDS in the workplace policies but also its educational programs and attitudes as a basis for being able to establish any response trends.

The selection of an appropriate union raised a number of issues to be considered. While it could be anticipated that the trade unions' parent body, the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) would have played an important part in framing initial union policies and strategies in relation to AIDS in the workplace, there is a strong possibility that some unions, because of the nature of their memberships, have been much more actively responsive to the need for AIDS-related workplace policies than others. Trade unions where the issue of AIDS in the workplace has been more immediate and urgent than in other unions - for example, from a potential transmission by injury point of view, health care workers could be seen as being at the "high risk" end of the spectrum whereas white collar trade unions such as teachers' unions might be seen as being at the "low risk" end - could be anticipated to have responded more rapidly and in greater detail than those whose members might be seen as facing significantly less workplace-related risks. Thus, it was concluded that the most appropriate union to study was likely to be one whose members might be drawn from occupational situations which varied from one end of the potential "risk spectrum" to the other.

A logical choice seemed to be a trade union which covered workers in many different areas of employment and where AIDS might be seen to have been of variable significance to workers in those diverse occupational areas. Thus, I chose the Australian Liquor, Hospitality and Miscellaneous Workers Union (LHMU) since the members of this union, and its predecessor, the Federated Miscellaneous Workers Union (FMWU), were drawn from so many different areas of work, including those where AIDS might be seen as a representing a significant work-related risk, that it would be reasonable to expect the membership, as a whole, to be exposed to the full range of work-related AIDS risk levels. The current membership characteristics of this Union are further elaborated in Chapter 3 which presents a brief historical overview of the evolution of the Australian Liquor, Hospitality and Miscellaneous Workers Union.

In order to investigate the policies developed by the Australian trade union movement in response to the advent of the AIDS epidemic, it is necessary to have a clear understanding of what policy involves both in theory and in practice.

Policy is defined by the Concise Oxford Dictionary (1990) as "a course or principle of action adopted or proposed by a government, party, business, or individual etc." ( p. 876). However, a very general definition of this kind tends to conceal many of the important aspects and issues associated with policy formulation and implementation. There are now so many issues involved in defining policy and understanding its theoretical underpinnings, development, application and evaluation that, during the past thirty or so years, an extensive policy-related literature has been generated. Universities now teach students politics and those who wish to be involved in policy making during their working years how to analyse policy, how to interpret its intent, how to carry it out or how to abandon it when it is seen to be unworkable or when the reasons for adopting a particular policy have been accomplished (Hogwood & Gunn, 1984). Yet, in spite of these developments, "there has been no consensus about what constitutes a ‘policy' ... no single accepted method of inquiry, and little agreement about the boundaries of a field called ‘public policy'" (Davis, Wanna, Warhurst & Weller, 1988, p.3).

Within the context of everyday living, the word ‘policy' is certainly a familiar one. As Gardner and Barraclough (1992) acknowledge:

In the mass media we daily encounter references to government policy on a range of topics. On a very general level we may read or hear of the Australian government conducting foreign policy, or immigration policy, or of a particular state government's rural development policy. At times the reference is far more specific and we are able to read of the intricacies of a particular policy, say on the administrative decentralisation of a particular government's health responsibility, or plans by the Australian government to integrate re- patriation hospitals into the health care systems of the various states. (p. 4)

Nor is use of the word ‘policy' restricted to the affairs of a nation or state, as a visit to the headquarters of any major organisation (such as a trade union) will reveal.

However, as Gardner and Barraclough (1992) point out, the ubiquity of policy in our everyday lives carries with it some pitfalls:

There is a danger of being seduced into thinking that a particular document, or statement, represents a distillation of all planning, debate and controversy on a particular matter and is somehow the ‘final word' on that issue. ... The student of policy should never accept any document as the ‘last word' but should examine the document in its wider context, looking for decisions and actions which can themselves be seen to constitute policy in a given area. (p. 5)

As indicated in the Concise Oxford Dictionary's definition, policy development is something which can be undertaken by an individual, an organisation or organisations, politicians (who are very often advised by their bureaucrats), or by any combination of these. Ideally then, a working definition of policy should be sufficiently broad to encompass all of these possibilities. While the definitions offered by many authors still tend to focus on particular kinds of policy development and the features which are associated with them, some attempt to take a broader perspective.

Hill and Bramley (1986), for example, drawing on elements of definitions offered by other authors, define policy as "a set of interrelated decisions taken by a political actor or group of actors concerning the selection of goals and the means of achieving them within a specified situation where these decisions should, in principle, be within the power of these actors to achieve" (p. 17). Hill and Bramley contend that this definition is useful because it is carefully phrased to emphasise a number of key features of public policy. Firstly, policy is virtually synonymous with decisions. However, as Hill and Bramley point out, an individual decision in isolation does not usually constitute a policy; rather, it is patterns of decisions over time, or decisions in the context of other decisions, which make a policy. Secondly, political decisions are taken by political actors, whether or not the people in this role are formally designated as politicians (for example, public servants as well as parliamentarians may make policy). According to Hill and Bramley this interpretation implies that it is the nature of decisions which makes them ‘political', and this, in turn, is what defines the actors as political. Thirdly, policies are about both means and ends. Fourthly, policies are contingent in the sense that they refer to and depend upon a ‘specified situation'. As the authors acknowledge, exactly how the boundaries of this situation may be interpreted is one of the many fine points around which many policy debates may rage: for example, how far a commitment to maintain health service expenditure may be contingent upon economic and financial considerations. Finally, the definition restricts policy to things which can (at least in principle) be achieved, in other words to matters over which those developing the policy have authority, and/or to actions/outcomes which are practically feasible. As Hill and Bramley stress, this is a very significant restriction, which raises issues about, among other things, policies which may be ‘symbolic' in the sense of not being seriously intended to be achieved in practice.

In an effort to identify the many uses of the word ‘policy', Hogwood and Gunn (1984) have suggested a categorisation of the term into some ten different categories including: use as a label for a broad field of activity such as foreign policy or economic policy; as an expression of general purpose or desired state of affairs as in such pronouncements as ‘Health for All by the Year 2000'; specific proposals such as those found in certain statements of the plans of governments; decisions of government by which a pattern of related decisions is seen to constitute policy; as a program (for example, a health screening program); as an output, that is, what government actually delivers (say, in terms of resources allocated) rather than merely promises to deliver; as an outcome, that is, what is actually achieved. As Hogwood and Gunn acknowledge, the distinction between output and outcome is often blurred and difficult to make in practice. However, as Gardener and Barraclough (1992) point out, "... it is important to seek to distinguish one from the other. For example, in the area of health it has become painfully obvious that outputs in the form of increased expenditure on curative services do not always lead to improved general levels of health in the wider population" (pp. 5-7).

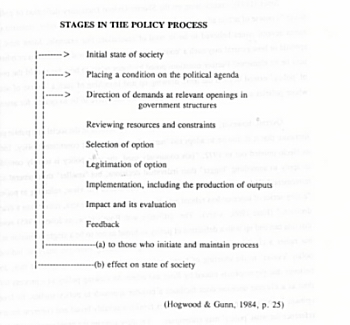

In order to facilitate a greater understanding of policy development, implementation and evaluation Hogwood and Gunn (1984) outline several policy process frameworks. The following diagram, which presents the policy process as a series of closely related stages, provides a useful insight into the dynamic nature of the policy process.

As noted earlier, policy development may be initiated by individuals and organisations as well as by governments. One of the most frequently used methods is the attempted exertion of pressure on formal policy processes by activist groups made up of individuals who share common interests. The activities of such pressure groups often push policy makers in directions which they had initially not intended to travel. One such group, having direct relevance to AIDS policy making, both in Australia and overseas was (and still is) a group called ACT UP (AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power). While more will be said about this group at a later stage, it is sufficient here to say that policies may be initiated or even significantly altered by pressure groups acting in the interests of the community or communities they purport to represent.

Jones (1985), commenting on the Shorter Oxford Dictionary definition of policy as being "a course of action adopted and pursued by a government, party, ruler, statesman, etc" raises several issues believed to be in need of resolution: For example, Jones asks, How specific or how general may such a ‘course of action' be and how discontinuous or otherwise may be its elements? Further questions posed by Jones relate to how far should the concept of ‘policy' extend beyond the mere drawing up and launching of such a ‘course of action', whose policies actually count, and how ‘public' do they have to be to qualify for attention.

Overall, however, there seems to be general agreement in the social and public policy literature that it is unwise to adopt too ‘narrow' a view of what constitutes policy. Indeed, as Heclo pointed out in 1972, "(a)s commonly used, the term policy is usually considered to apply to something ‘bigger' than individual decisions, but ‘smaller' than general social movements" (Heclo, 1972, p. 84). Rose (1969) also shares this view, referring to policy as "a long series of more or less related activities and their consequences, rather than a discrete decision." (Rose 1969: x xiv). The difficulty with Rose's view, as Jones (1985) notes is that one can end up with a definition of policy so broad as not to be a single definition at all, but rather a cluster of definitions encompassing everything from the study of individual policy ‘events' to the charting of broad policy ‘trends' over time. In spite of this, Jones believes that the emphasis placed by Rose and others on viewing policy as a process rather than as a discrete decision does facilitate a broader approach to policy studies. In Jones's opinion "a ‘policy as process' approach does furnish a suitably broad and coherent frame of reference for what ‘policy' may encompass ... Yet there remains the problem of deciding just how far to cast the net when it comes to deciding just which activities, and hence which attendant factors, are usefully to be considered as having a bearing upon policy" (Jones, 1985, p. 13).

Clearly in this study, I am interested not so much in what Jones (1985) describes as "mere ideas, proposals, or ‘paper plans' that stand no chance of being put into operation and hence of impinging on social conditions" (p. 13), but rather in policy as a tangible product of interaction between a number of quite diverse elements of Australian society.

As the above discussion reveals, when it comes to defining what is meant by the word ‘policy', each body, group, and organisation tends to have its own interpretation of what it means. In turn, each interpretation will have its own implications for how the resulting policy/policies will be used.

For the purposes of this study, the concept of ‘policy as process' seems to offer the most constructive way of approaching AIDS-related policy development because of the many contributors who have been involved since AIDS was first diagnosed in Australia not so many years after its initial diagnosis in the United States of America.

The Australian Federal Government responded swiftly when it became clear in the early 1980s that it had an epidemic of potentially major proportions on its hands (Timewell, Minichiello & Plummer, 1992). In an article published in 1992, Altman tells how Dr Neal Blewett, Federal Minister for Health from March 1983, "once recounted how, in his initial briefing, the new disease was mentioned, but almost as something of a joke. Within two years it had become a major preoccupation of government policy, one in which Blewett played perhaps a more significant role than any other health minister in the world." (Altman, 1992, p. 56).

In 1983, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) established a Working Party on AIDS, then, in 1985, the Working Party was reconstituted as the National AIDS Task Force and charged with responsibility for providing information and advice which could be used as a basis for national policy development and review. In addition, Dr Blewett established his own ministerial advisory committee, the National Advisory Committee on AIDS (NACAIDS). (Altman, 1992). These initiatives clearly demonstrated that the Federal Government was taking the challenge of what was now perceived as the AIDS crisis seriously, and was determined to establish policies aimed to try to prevent the spread of the disease within the Australian community.

It had quickly become obvious that, unless prompt and effective action was taken without delay, the public health system of the country was going to be sorely tried. As Altman (1992) notes, if AIDS was about to affect large numbers of people in the Australian community, appropriate educational programs had to be designed and implemented to increase public awareness of the disease and the kinds of strategies which could be used to restrict its spread had to be implemented before health care costs, especially hospital costs, escalated out of control. This meant that policies had to be devised to inform and instruct all members of the community, workers and management included (Timewell, Minichiello, & Plummer, 1992).

As the main purposes of this investigative study are to explore and place on record the policies developed by the trade union movement in relation to work-related aspects of AIDS within the community from the earliest years of the epidemic's presence in Australia, the policies relating to other aspects of AIDS will not be dealt with, except where they impinge on workplace-related issues and arguments.

In view of the number of trade unions affiliated to the umbrella organisation, the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), it seemed likely that that organisation would logically have been an initial source of workplace-related AIDS policies and/or directions in Australia.

A document search revealed that, at its meeting on 23-25 February 1988, the ACTU Executive endorsed its first formal policy on AIDS. Contained in this document is the following statement:

The particular issues addressed in the document are: (1) Occupational health and safety; (2) Education and training, and; (3) Protection of employees, and the stated position of the ACTU at that time was that the the most effective way of controlling the spread of the virus is through education rather than legislation.

An admittedly brief search undertaken at the ACTU headquarters in Melbourne in early April 1995 did not yield any evidence to suggest that the ACTU had taken any further direct role in advancing the establishment, through the trade union movement, of AIDS-related policies in Australia. However, there seems to be little doubt that the ACTU's AIDS policy provided the basis for the policies subsequently adopted by the various trade unions. For example, the Federal Council of the Miscellaneous Workers Division of the Australian Liquor, Hospitality and Miscellaneous Workers Union, produced their policy on AIDS for endorsement by the Union's Federal Executive in July of 1988. That document states that the LHMU endorses the ACTU policy on AIDS as adopted at the February (1988) meeting of the ACTU Executive, including the following:

The ACTU recognises that HIV infection, which may lead to AIDS is only one of a range of communicable diseases which workers may be exposed to. However, it is noted that there are only isolated circumstances in which people are exposed to the AIDS virus in an occupational setting i.e. health care industry. (Federal Executive Report: AIDS, 1988, p. 14)

Because the LHMU did not add anything further to the ACTU document, it apparently chose to adopt the Council's policy in toto.

Before setting out to examine, in detail the relevant records of the union chosen as the focus for this investigative study it was necessary to locate and review the available literature on the general topic of AIDS and the trade union movement. The product of these activities is presented in the next chapter.

| Photos

of the Groves |

Mannie has a personal web site: RED JOS: HUMAN RIGHTS ACTIVISM

Mannie's blogs may be accessed by clicking on to the following links:

MannieBlog (from 1 August 2003 to 31 December 2005)

Activist Kicks Backs - Blognow archive re-housed - 2005-2009

RED JOS BLOGSPOT (from January 2009 onwards)

This page updated 18 MAY 2014 and again on 8 MARCH 2022

PAGE 36